Will Russian-Afghan Logistics Dictate Foreign Policy?

BY Herschel SmithWe have raised the issue of Georgian and more broadly European involvement in the search and decision-making for a new logistics line for Afghanistan. As to the proposed supply line through Georgia, we observed that:

… interestingly, this leaves us vulnerable yet again to Russian dispositions, even with the alternative supply route. Georgia is the center of gravity in this plan, and our willingness to defend her and come to her aid might just be the one thing that a) kills the option of Russia as a logistical supply into Afghanistan, and b) saves Georgia as a supply route. Thus far, we have maneuvered ourselves into the position of reliance on Russian good will. These “thawed relations” might just turn critical should Russia decide again to flex its muscle in the region, making the U.S. decisions concerning Georgia determinative concerning our ability to supply our troops in Afghanistan. Are we willing to turn over Georgia (and maybe the Ukraine) to Russia in exchange for a line of supply into Afghanistan, or are we willing to defend and support Georgia for the preservation of democracy in the region and – paradoxically – the preservation of a line of supply to Afghanistan?

Stratfor weighs in on the logistical maelstrom (at the time of writing of this article, the Stratfor analysis was still available through Google organic search, but not by direct URL for non-registered users).

With little infrastructure to the east, the Pentagon is forced to go north, into Central Asia. Though some fuel is shipped to Western forces in Afghanistan from Baku across the Caspian Sea, there is little indication that existing shipping on the Caspian could expand meaningfully. Additionally, there would be the challenge of transferring cargo from rail to ship back to rail on top of the ship-rail-truck transfers that are already required in Afghanistan.

But even if Caspian shipping was not a problem and if there was sufficient excess seaworthy capacity, there remains the problem of Georgia. Though politically amenable at the moment, it is unstable; furthermore, with some 3,700 Russian troops parked in both Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Russian military forces are poised to sever the country’s east-west rail links.

These realities will likely drive the logistical pathway farther north, through Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan and through Kazakhstan to Russia proper (some U.S. transports already utilize Russian airspace).

Turkmenistan presents its own challenges, as it is particularly isolated after years of authoritarian rule and continues to suffer from the legacy of what was essentially a state religion of worshipping the now-deceased Turkmenbashi. His successor, Gurbanguly Berdimukhammedov (who is rumored to be the Turkmenbashi’s illegitimate son), continues to struggle to consolidate power and is left with a series of delicate internal and external balancing acts. In short, enacting new policies under the new government remains problematic to say the least.

There is another choice: Use a Russian or Ukrainian port of entry where organized crime will be a particularly serious problem (as well as espionage with any sensitive equipment shipped this way), or use a more secure — and efficient — port that will require a rail gauge swap from the European and Turkish 1,435 mm standard to the 1,520 mm rail gauge standard in the former Soviet Union.

All of this is complicated, but the linchpin is working out an agreement to use Russian territory. This presents an even more profound challenge than Russia’s real (but not unlimited) capacity to meddle in its periphery.

While there are a number of outstanding questions — where exactly U.S. supply ships might dock to offload supplies, whether a transfer of cargo from the Western to Russian rail gauge might be necessary, whether the route would transit Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan or both, etc. — these are minor details in comparison to the Russian problem. If there is an understanding with Moscow, the rest is possible. But that understanding must entail enough reliability that Russia cannot treat U.S. and NATO military supplies like natural gas for Europe and Ukraine.

Without an understanding between Washington and Moscow, none of this is possible.

The problem is that while the Kremlin has been reasonably cooperative up to this point when it comes to U.S. and NATO efforts in Afghanistan, such an understanding may not be possible completely independent of the clash of wills between Russia and the West. There is too much at stake, and the window of opportunity is too narrow for Moscow to simply play nice with the new American administration without a much broader strategic agreement and very real concessions. Nevertheless, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe, U.S. Gen. Bantz Craddock, has been making overtures to Russia about improving relations.

General David Petraeus is also involved in the efforts to line up a logistics pathway to Afghanistan. “The top US military commander for the Middle East and Central Asia has denied reports the US is planning to open a military base in Kazakhstan.

Speaking in the Kazakh capital, Astana, Gen David Petraeus also said the US had no plans to withdraw its military presence from neighbouring Kyrgyzstan.

The general is in Kazakhstan for talks on the role of Central Asian states in supporting America’s Afghan operations.

Gen Petraeus and Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev discussed the partnership between their countries, and Kazakhstan’s role in supporting US operations in Afghanistan. Kazakhstan has recently signed an agreement allowing the transit of non-military US supplies to Afghanistan.”

Assuming the veracity and accuracy of this report, it would appear that the probability is that the chosen line of supply directly involves Russia, although only for so-called “non-military” supplies.

But this choice might burden any upcoming decisions on the Ukraine and Georgia and whether they are allowed to enter into NATO, as well as other important European issues such as whether missiles will be deployed in Poland. While not learning much from the Stratfor analysis, they are on target with their analysis of the affects of the decision-making as it pertains to Russia.

Stratfor says “there is too much at stake, and the window of opportunity is too narrow for Moscow to simply play nice with the new American administration without a much broader strategic agreement and very real concessions.” Concessions indeed. And while the route selected will be moderately to significantly less problematic that the alternatives, and while Gates, Petraeus and Craddock might actually believe (for now) in Russian good intentions, they should remember that Russia is ruled by ex-KGB, bent on regional hegemony for at least what they consider to be their near abroad.

The alternative through Georgia still exists, as long as the U.S. is willing to play hard ball and defend her sovereignty (as well as defend her as a line of logistical supply to Afghanistan). More specifically, the line of supply is as follows. First, supplies (including military supplies) would be shipped through the Mediterranean Sea through the Bosporus Strait in Turkey.

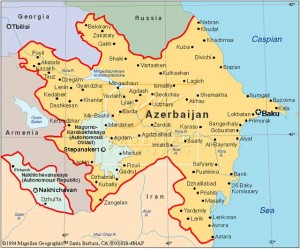

And from there into the Black Sea. From the Black Sea the supplies would go through Georgia to neighboring Azerbaijan.

From here the supplies would transit across the Caspian Sea to Turkmenistan, and from there South to Afghanistan. A larger regional map gives a better idea of the general flow path.

The problems are numerous, including the fact that the supplies would be unloaded in Georgia to transit by rail car or road, unloaded from rail or truck to transit again by sea, and finally loaded aboard rail cars or trucks again (after passage across the Caspian Sea) in Turkmenistan to make passage to Afghanistan.

But it isn’t obvious that this line of supply is impossible, however impractical it may be. U.S. military leadership should remember that an alternative exists to the Russian line of supply to Afghanistan. It will be too late to act to secure a line of supply through Georgia at some point in the future, but until then, the U.S. should carefully examine the Russian demands for this logistical aid. The Russian demands are likely to evolve and expand, and it is this expansion that will prove to be troubling. Russia is playing nice now. This won’t last forever.

Prior:

New Afghan Supply Route Through Russia Likely

U.S-Georgia Strategic Partnership

The Logistical Battle: New Lines of Supply to Afghanistan

The Search for Alternate Supply Routes to Afghanistan

Large Scale Taliban Operations to Interdict Supply Lines

More on Lines of Logistics for Afghanistan

How Many Troops Can We Logistically Support in Afghanistan?

Targeting of NATO Supply Lines Through Pakistan Expands

Logistical Difficulties in Afghanistan

Taliban Control of Supply Routes to Kabul

On January 30, 2009 at 8:12 am, Bob Sykes said:

The news yesterday indicated that the Polish missiles will not be built.

On January 30, 2009 at 9:41 am, Herschel Smith said:

Yes, I had noticed myself, but thanks for pointing this out Bob. I am not so convinced that the missiles are the biggest indicator of the future of relations with Euro-Russia (althought they are one of many), but that NATO membership for Georgia and the Ukraine is the real test. They will remain hopelessly tied to the old Soviet model unless allowed to join NATO. I and my readers will be watching.