Yochi J. Dreazen opines in the Wall Street Journal concerning how the U.S. strategy in Afghanistan hinges upon far-flung outposts. A few salient parts follow.

“You can’t commute to work in counterinsurgency,” Gen. Petraeus told a security conference in Munich. He declined requests to be interviewed for this article.

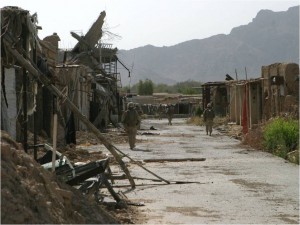

Afghanistan, however, is different from Iraq. It remains a destitute country with few roads and virtually no modern infrastructure, meaning the outposts are unusually isolated. Outposts in Iraq were located in major cities, so they were able to protect the vast majority of the Iraqi populace. In Afghanistan, most outposts are in rural areas like Seray. Often, these outposts can be reached only by air. That has prompted fears the bases could theoretically be overtaken by insurgents before reinforcements can arrive.

The article then turns to Wanat as an example of what can happen in what he calls “far-flung outposts.” More on this in a minute. Continuing with Dreazen’s article:

David Kilcullen, a counterinsurgency expert who has long advised Gen. Petraeus on Iraq and Afghanistan, supported the outpost strategy in Iraq. But he says the U.S. is making a mistake by deploying so many troops to remote bases in Afghanistan.

Mr. Kilcullen, a retired Australian military officer, notes that 80% of the population of southern Afghanistan lives in two cities, Kandahar and Lashkar Gah. The U.S. doesn’t have many troops in either one of them.

“The population in major towns and villages is vulnerable because we are off elsewhere chasing the enemy,” he said.

Andrew Exum picks up on this theme and poses a number of questions.

Afghanistan is a really big country — bigger than Iraq — and we are trying to protect more terrain with fewer troops. The old maxim that he who defends everything defends nothing seems to apply here. Are we, by putting troops in little far-flung outposts, setting them up for more Wanats? Should we instead be camped out in the big cities of Kabul, Kandahar and Lashkar Gah as Kilcullen suggests? Should not our first priority be to secure the Afghan people in order to reduce violence in the country and facilitate the upcoming national elections?

Joshua Foust responds to Exum’s questions thusly.

Umm, should not. The last people to assume that “the people” reside in the cities, and so there their operations should focus, were the Soviets. The Taliban run circles around the U.S. and ISAF precisely they control most of the countryside and not the cities. The problem isn’t Kabul, but the Tagab. The problem isn’t Kandahar but the hills above it. The problem isn’t Lashkar Gah, but Garmser. The problem isn’t Khowst, but Spera. The problem isn’t Herat, but Shindand. The problem… well, you get my point (and that list wasn’t meant to be comprehensive, merely illustrative, in case that weren’t obvious). If you want to do a population-centric COIN in Afghanistan, you do it in the countryside …

… this kind of flabbergastery is perfectly emblematic of why knowing buzzwords like “population-centric counterinsurgency” is really worthless without that other COIN buzzword, “intimate knowledge.” You can’t make a strategy population-centric if you don’t know the population, COINdinistas.

Without considering nuance and detail, it is easy to conflate issues. We have extensively covered the Battle of Wanat, and while the base may have been “far-flung,” close air support was initiated within 27 minutes of the start of the battle, close combat aviation within 62 minutes, and reinforcement and relief within approximately 2 hours. The Battle of Wanat happened and proceeded as it did in large part due to other decisions: Eight of the nine who perished did so as a result of defending Observation Post Top Side, U.S. forces didn’t occupy or control the high ground, intelligence failed as indications of massive Taliban troop movements were ignored, and a host of other issues.

Wanat is a sidebar discussion regarding the overall strategy of the campaign. So who is right? Should we protect the population in large urban centers as suggested by Kilcullen (and questioned by Exum), or is Foust right that properly engaging Afghanistan means doing so in the countryside? The answer means everything to the campaign.

First off, it is important to correct wrong impressions that this information can give. The U.S. doesn’t have troops in Kandahar, for instance, because that is a Canadian operation under the purview of the ISAF. Canada currently has approximately 2700 troops in Kandahar, and this force presence is soon to double with the addition of a U.S. BCT.

Furthermore, part of the 10th Mountain Division is now garrisoned near Kabul in Maidan Wardak and Logar provinces to the south of Kabul. So it simply isn’t true that the U.S. forces are all going to far-flung outposts as opposed to securing the population centers.

But at what price? At Forward Operating Base Altimur, the 10th Mountain has access to Lobster tails, massage services, skype hookups, jewelry shops and six kinds of ice cream. While no one should begrudge them their creature comforts, the most problematic of all concerns is that they are said to be “bored.” So should these troops be in more rural locations instead of urban centers?

This debate falls into the trap of Clausewitz – that of trying to find a unitary focus for our efforts. Both Exum and Foust favor a population-centric model, and yet The Captain’s Journal supports a different view. U.S. forces are present in Afghanistan because there are enemies of the U.S. located there, and also those who harbor enemies of the U.S. Without them, the likelihood of our presence is vanishingly small. The enemy is our target.

If the enemy announced his presence and fought without the benefit of mixing with the population, the rate of the fight would be more productive. This has occurred even recently in Afghanistan, when the Taliban evacuated Garmser of its population, dug in and unsuccessfully faced down the Marines of the 24th MEU. During their deployment in Helmand, they killed some 400 hard core Taliban fighters in what was described at times as “full bore reloading.” Yet the tribal elders also said that “When you protect us, we will be able to protect you,” showing little interest in reconstruction, programs and assistance.

But it will not always be this clear. The enemy is who we are after, but to get to them at times requires focusing on the population. Every situation is unique, and thus rather than finding a center of gravity, it is best to see the campaign as employing lines of effort. In spite of the lack of adequate troops, the campaign will not be an either-or decision, focusing on the enemy or the population. It will be both-and.

Foust is right. The Russians focused on the large population centers, and left the countryside to the Taliban. But Exum is also right to question only deploying in rural areas. Kandahar has seen its share of troubles, and even the Canadians admit that the sense of security has plummeted because of Taliban activity. The Taliban are there in force, the population has no security, and thus a force presence is required in Kandahar.

No single narrative is adequate to describe what is required to successfully prosecute the campaign, and buzzwords add little if anything to the discussion. We must be smart and allow the local situation to dictate the plan of action. Whether from tribal elders in Garmser or the more sophisticated population of Kandahar, the message is the same. The enemy cannot be allowed to rule the population.