Capturing Insights from Firefights to Improve Training

BY Herschel SmithFrom National Defense:

There is a popular belief that soldiers have a significantly longer life expectancy in a combat zone after they have survived their first few firefights. But little research has been conducted to evaluate what soldiers learn early in their deployments that would make the difference between improved effectiveness and becoming a combat fatality.

Can learned factors or perhaps inherent traits be replicated and conveyed in training so that a soldier’s chance of surviving initial firefights is similar to that of a seasoned combat veteran?

Past anecdotal discussions have indicated that military units tend to suffer higher casualty rates in their first engagements with the enemy. Recent research demonstrates that the first 100 days of combat is a more reliable critical period for improving the likelihood of survival than the widely held “first five firefights” theory.

These results hold implications for several aspects of modern training, as well as tactics, techniques and procedures used by today’s military.

The findings are the result of a study commissioned by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

The study sought to determine the most likely times within a tour of duty that a soldier might become a combat-related fatality. The research also aimed to identify methods for reducing fatalities associated with these vulnerable times during a soldier’s deployment.

Statistics are not kept on the number of firefights in which a soldier experiences. In addition, a commonly accepted definition of firefight was difficult to ascertain, further complicating an investigation of the “first five” concept.

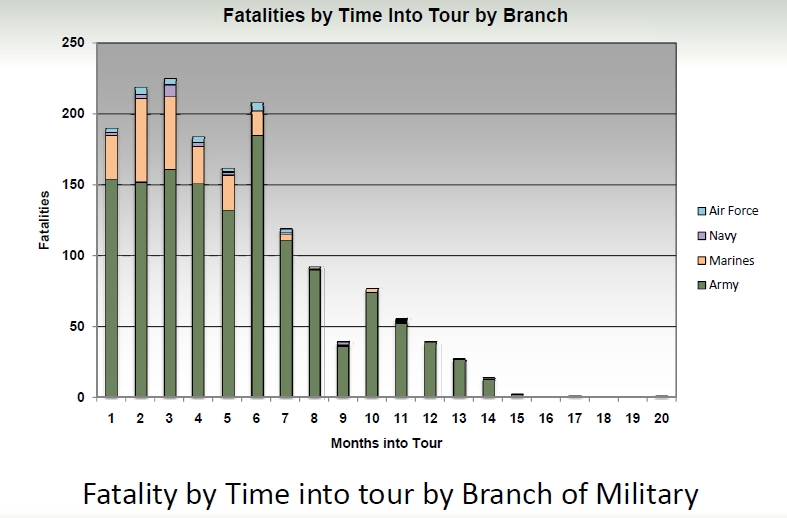

Based on analyses of databases covering all publicly available U.S. and U.K. fatalities over the past three years, nearly 40 percent of fatalities occur in the first three months of deployment.

One potential factor is troop transitions, such as old units rotating out and new units learning the ropes as they rotate in. Loss of local intelligence when an old unit leaves can be a crucial factor affecting fatalities during these initial months. When the old unit departs, relationships with locals are frequently lost. Lack of familiarity with the environment and enemy tactics, as well as a general lack of experience, are also important factors.

Analysis revealed another increase in Army fatalities, though not as dramatic, at approximately the six-month mark of a tour. The six-month spike was less pronounced for Marines, Navy and Air Force personnel. In addition, a minor spike in fatalities occurred again for soldiers at the 10-month mark. Likely factors for the increase in fatalities in these later months are fatigue, complacency and stale tactics. Frequent missions and patrols, overly consistent day-to-day procedures, and lack of in-theater training to maintain soldier focus may exacerbate these factors as well.

The graph above comes directly from Capturing Insights from Firefights to Improve Training, a DARPA presentation which I obtained from Scott Scheff with HFDesignworks. There are several interesting and noteworthy observations from the study. The spike at six months for Marines is not less likely as National Defense claims. It is non-existent. The spike occurs only for Army deployments. Unstated is whether seventh month deployments versus 12- or 16-month deployments for the Army have anything to do with these metrics.

Regardless of why this spike occurs for Army and not the Marines, the message is clear from the study. Stale tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) allows the insurgents to train themselves to our routines. There are a number of tools recommended by the team which could contribute to better metrics (whether two-month or six-month). The team recommends better just-in-time training (or what they call immersion training), a longer overlap from deployed to entry units, training to avoid complacency, theater- and situation-specific weapons deployment, and most importantly, revision of tactics, techniques and procedures to avoid stalemates between insurgents and counterinsurgents near or before the six-month period. This is extremely important.

This follows the article entitled Marines, Taliban and Tactics. Techniques and Procedures. Better training and preparation for and during deployments means lives saved.

On April 21, 2010 at 7:51 am, Warbucks said:

While the statistics seem to present rather stubborn facts, aviation tends to have its own set of statistics occurring around 500 hours of accumulated flight time. For this reason and for the development of enhanced pilot cockpit and situational combat awareness, I been a strong advocate of extraordinary play time for pilots in combat simulators.

I came across this letter some while back. I believe the letter is still valid these many years later:

Commanding General

Marine Corps War Fighting Lab

3255 Meyers Avenue

Quantico, VA 22134

Re: Training enhancements to combat readiness through computer

simulation.

Dear Gen. XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

I served on active duty in the mid-60’s as a US Marine fighter pilot.

Recently I have become skilled at WWII fighting techniques, air-to-air

combat engagements, using Microsoft Combat Flight Simulator 3.1a. My rapid rise in skill proficiency and successful tactical elections in game

playing offers valuable combat readiness enhancement training insights that would have served me well on active duty. The cost to me was 300 hours of on-line combat scenarios. My conclusions are, there exist considerable training enhancements to combat readiness through computer simulation. There are three findings of note.

In their order of significance on why computer simulation would seem to

improve combat readiness:

(A) GROUP ENGAGEMENTS YIELDS “THE WINNING SCENARIO.” After some short while of training, group enemy engagements become intuitive immediately with a sense of personal confidence retained while approaching the battle. The pilot learns to execute the right maneuvers as required. The pilot learns to think several moves ahead and starts thinking 4 dimensionally (3 dimensions of space and 4th dimension of timing on what to do next augmented by continuing relevant real time input).

Approaching a group of enemy combatants of say 3-to-1 in their favor against my 1 aircraft, I often win and take out the entire enemy group, or a string of wins against the same group, exceeding 10 to 1.* The player learns to prioritize opponents always dealing next with the remaining highest threat level. Grabbing the relevant input quickly to modify tactics from each evolving battle field yields a winning scenario.

I found I need to participate in the real (computerized) engagement to learn from the experience. I am not disposed to think through clearly and reliably all possible forms of combat engagement ahead of time, even though my interest level for aviation, the game, and combat tactics remain strong. I need to do it to know it.

A combat pilot would not survive long enough to learn through real combat experience that learned through simulation. I now understand intuitively “the winning scenario” given any combination of enemy groupings posed against me. I gained this understanding gradually through hundreds of computer simulation on-line enemy engagements, solo and on teams.

(B) KNOW THE ENEMY AND KNOW YOURSELF. Much of my live missile training should have yielded personal understanding and confidence in the Sparrow missile performance and capability, which it did not. Training in dog fighting tactics on the other hand were marginal and slow at best. By the time I was discharged, I was beating all squadron newbies, holding my own or better with my peers, but none of us seemed equal to a graduate of Top Gun advanced fighter school. Computer simulation of the sort available today simply did not exist in 1965. Robust, combat computer simulation, with high level reality, repeated many times, would have yielded far greater tactical readiness in us all, when combined with live, in-field, training exercises. Through high-realism computer simulation the pilot lives long enough to actually learn the strengths and weaknesses of each enemy aircraft, enemy weapon system, his own aircraft and his own weapon systems and learns the winning tactics to use for any given scenario. I believe we would have all been flying on par with a graduate of the famous Top-Gun combat fighter school had we augmented our training with computer simulation.

(C) ATTITUDE ADJUSTMENT. The pilot enters combat with confidence linked realistically to likely outcome and better disposed to quickly adapt and respond correctly to any threat level.

*There is a humiliation factor delivered through repeated losses that

prompts some players to quit and not return, or there would be even higher win ratios.

The only caution I would raise is that on some deep level, the subconscious mind can not distinguish between real combat and simulated combat. Game playing can lead the participant into a phase of “combat nerves” somewhat similar to real combat. It takes several weeks to re-cooperate from this transitional phase…. about 21 days for the subconscious to reset its sense of security.

On April 26, 2010 at 7:55 pm, bgaerity said:

Warfare, more or less, has always been idiosyncratic, requiring a big toolbox and rapid adaptation to an ever-changing context. We’re finally learning how to change more quickly but more emphasis will need to placed on self-learning and independent decision-making. This is true for all aspects of life, and should be part of a standard high-school curriculum. I don’t think we’ve fully made that adjustment yet. Our enemies will increasingly be smart, elusive, unconventional and difficult if not impossible to completely subdue. We’ll need to be smarter, faster, relentless and coordinated.