An interesting exchange occurred between David Kopel, Joyce Malcolm, et. al., and another professor on carry of guns in England. The first volley appeared at The Washington Post, and while I won’t quote in its entirety, I will quote at length and send you to the article for the conclusion.

Should D.C. residents have the same right to the licensed carry of defensive handguns as the people in most states? That is the issue currently before the D.C. Circuit, in Wrenn v. District of Columbia. The D.C. government lost on this issue in federal district court. D.C.’s brief to the D.C. Circuit argues that “For as long as citizens have owned firearms, English and American law has restricted any right to carry in populated public places.” According to the brief, the pre-existing right to arms, which was protected by the Second Amendment, “did not encompass carrying in densely populated cities.” Further, D.C. says that in the 19th century, carry prohibitions were widespread in the United States. An amicus brief on behalf of Michael Bloomberg’s organization “Everytown” makes similar claims.

In an amicus brief filed this week, several legal historians, including me, dispute the D.C. and Bloomberg claims. Besides me, the amici are Joyce Malcolm (George Mason Law; the leading historian on the history of English gun control and gun rights), Robert Cottrol (co-appointment at George Washington in Law and in History; a specialist in the history of race, including the racial aspects of gun laws), Clayton Cramer (author of three books and many articles on the history of firearms law in Early America and the 19th century) and Nicholas Johnson (Fordham Law; most recent book is Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms). Our attorneys were Stephen Halbrook and Dan Peterson. Halbrook has a 5-0 record in the U.S. Supreme Court, all on firearms law cases, and is himself a leading scholar on the legal history of the right to arms.

The claim that there was a general prohibition on the carrying of arms is based on the 1328 Statute of Northampton, which D.C. characterizes as a public carrying ban. As our brief explains, the case law is contrary to such a broad interpretation of the 1328 Statute. For example, Sir John Knight’s Case (1686) said that the statute applies only to “people who go armed to terrify the King’s subjects.” There was a lot of weapons-carrying in England, partly because of public duties, such as keeping “watch and ward,” as well as required target practice (in longbows and muskets) at the target ranges that every village was required to maintain. The peaceable carrying of arms was an ordinary thing to see, not a terrifying one.

In the American colonies, nobody appears to have thought that they could not carry arms because of a 1328 English statute. Rather, the colonies mandated gun carrying in certain situations, such as when traveling or when going to church. To the extent that a few early states (and later, D.C.) enacted statutes expressing common law restrictions on arms carrying, the statutes (like the common law) only applied when a person did so “in terror of the country.” (D.C. 1818 statute; similar language in the states). In the colonial period, and in the first 37 years of independence, there were no restrictions on concealed carry. Several states enacted concealed carry bans thereafter, but of course these did not limit open carry. Moreover, our first “four Presidents openly carried firearms.” The notion that they, or anyone else, thought Americans were prohibited from doing so by a 1328 English statute is implausible.

To this, Priya Satia responds at Slate.

Oddly enough, medieval English laws matter in legal debates about gun control in the United States today. The Supreme Court’s landmark 2008 Second Amendment decision, District of Columbia v. Heller, determined that sufficiently “long-standing” firearms regulations are constitutional. This means that in Second Amendment cases, we have to get our English history right.

Doing so is crucial in a gun case now before the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals: Wrenn v. D.C. The case is critical for Washington residents but also more broadly as the pro-gun lobby challenges laws in cities across the country. The District of Columbia argues that English and American law has always permitted restrictions on the right to carry guns in populated public places, tracing this tradition to the 1328 Statute of Northampton, which generally prohibited carrying guns in public. The District argues that the Second Amendment and its English precursors did not allow unfettered public carrying in densely populated cities, and thus the District may restrict it.

A group of legal historians has disputed this interpretation in an amicus brief filed this month, followed by an essay in the Washington Post by David Kopel, adjunct professor at Denver University’s law school. They claim the English Bill of Rights of 1689 superseded the 1328 statute and that, “There was a lot of weapons-carrying in England.” Thus, they conclude, D.C. residents have the right to carry guns in public. But their English history is wrong, as are their conclusions about public carry in the nation’s capital.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688–89 established a Protestant monarchy in England under William and Mary, ending the reign of the Stuarts. The Bill of Rights codified the constitutional limits on the new monarchy, including a provision guaranteeing Protestants (but not Catholics or Jews) the right to bear arms. But political realities overrode this provision. The new monarchy remained vulnerable to “Jacobites” seeking to restore the Stuart dynasty, with French and Spanish backing. This danger meant the British state could not permit widespread gun ownership.

The new monarchy’s disarmament laws built on laws passed after the Restoration of 1660, when the Stuarts returned to power after 11 years of republican rule and were similarly concerned with political stability. A 1670 statute had limited firearms possession to the noble and rich, although even their arsenals were subject to search and seizure at sensitive moments. A series of game laws from 1671 through 1831 dramatically reduced the number of people permitted to hunt, empowering gamekeepers to search for and seize unauthorized firearms. Smuggling laws also made carrying arms grounds for arrest. An armed militia was active through the 1680s, but not the 80 years that followed. Through the 1740s, its arms were locked in royal arsenals and distributed only at assembly. The government’s success at disarming the population made the militia superfluous, since its entire purpose was to prevent an armed rising against the government.

The amicus brief by Kopel et al. paints a picture of widespread gun carrying incongruous with this well-established history. The authors invoke the 1686 acquittal of the gun-toting Sir John Knight as evidence that the 1328 statute was inconsistently applied, but Patrick J. Charles, the award-winning historian for Air Force Special Operations Command, has shown that Joyce Malcolm (one of the brief’s authors) created this finding “out of thin air.” In fact, Knight was acquitted because he was armed while cloaked with government authority. In an era of rapid urban growth, before state provision of police, the wealthy and noble fulfilled the role of informal police.

And I think you see where this argument is going, i.e., justifying law enforcement use of weapons to the exclusion of everyone else, even the military. I wrote to Dave Kopel for a rejoinder, and he declined saying he had too many “irons in the fire,” but that “among its errors are conflating anti-hunting laws (which continued after 1689) with laws against defensive gun ownership.”

He also sent me to Joyce Malcolm, who is also busy but reminded me of her piece in Financial Times (I cannot locate the URL except at Free Republic).

Self-defence, William Blackstone, the 18th century English jurist, wrote, is a natural right that no government can deprive people of, since no government can protect the individual in his moment of need. The English Bill of Rights of 1689 affirmed the right of individuals “to have arms for their defence”. It is a dangerous right. But leaving personal protection to the police is also dangerous, and ineffective. Government is perilously close to denying people the ability to protect themselves at all, and the result is a more, not less, dangerous society.

I won’t rehearse the details of the debate. But one thing stands out to me in this exchange, and it’s Kopel’s statement that “The notion that they, or anyone else, thought Americans were prohibited from doing so by a 1328 English statute is implausible.” This is an important observation, so let’s unpack it a bit.

From my pedestrian point of view (from my coursework in philosophy, history and apologetics in seminary), I’ve always claimed that the best way to understand what the founders intended was to observe their lives and understand what they did or didn’t think their words meant. Look to the culture, context and milieu which created these men and their views. I have cited the public and open carry of weapons to which Kopel refers.

In the colonies, availability of hunting and need for defense led to armament statues comparable to those of the early Saxon times. In 1623, Virginia forbade its colonists to travel unless they were “well armed”; in 1631 it required colonists to engage in target practice on Sunday and to “bring their peeces to church.” In 1658 it required every householder to have a functioning firearm within his house and in 1673 its laws provided that a citizen who claimed he was too poor to purchase a firearm would have one purchased for him by the government, which would then require him to pay a reasonable price when able to do so. In Massachusetts, the first session of the legislature ordered that not only freemen, but also indentured servants own firearms and in 1644 it imposed a stern 6 shilling fine upon any citizen who was not armed.

When the British government began to increase its military presence in the colonies in the mid-eighteenth century, Massachusetts responded by calling upon its citizens to arm themselves in defense. One colonial newspaper argued that it was impossible to complain that this act was illegal since they were “British subjects, to whom the privilege of possessing arms is expressly recognized by the Bill of Rights” while another argued that this “is a natural right which the people have reserved to themselves, confirmed by the Bill of Rights, to keep arms for their own defense”. The newspaper cited Blackstone’s commentaries on the laws of England, which had listed the “having and using arms for self preservation and defense” among the “absolute rights of individuals.” The colonists felt they had an absolute right at common law to own firearms.

And further:

Their laws about children and guns were strict: every family was required to own a gun, to carry it in public places (especially when going to church) and to train children in firearms proficiency. On the first Thanksgiving Day, in 1621, the colonists and the Indians joined together for target practice; the colonist Edward Winslow wrote back to England that “amongst other recreations we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us.”

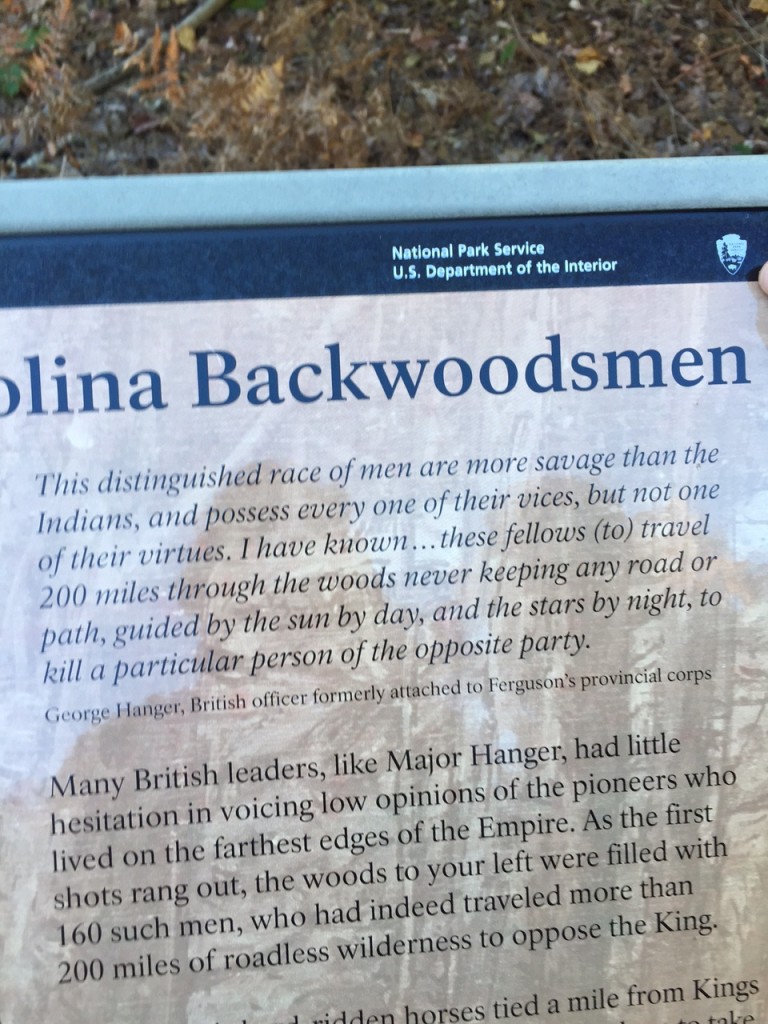

The ownership and carry of weapons was virtually ubiquitous in colonial America. It was so for the purposes of hunting, defense against animals, and defense against men. As my own professor C. Gregg Singer has pointed out, news reports, primary source literature and eyewitness accounts are the best information on colonial America. All information and data points to the expectation of the duty of self defense, rather than a prohibition of such.

Moreover, while I concede that it’s interesting what English law had to say about ownership and carry of weapons, it isn’t determinative. We follow the constitution, and in particular, I have asserted before that rights to ownership and carry of weapons follows God-given stipulations, the constitution flowing from it’s basis in this moral history.

If Satia’s goal was to persuade me that I could look to England to find basis to reject ownership and carry of weapons, the goal wasn’t met. The attempt was an abject failure.