I have certain incorrigible views of covenant and sovereignty that have their genesis in my Calvinian theology, and it is always interesting to observe and study how men relate to one another and to God. But before we get to that, let’s begin with what’s happened in the narco-trafficking world. This analysis promises to be lengthy and perhaps even tedious, so if you intend to make it through a sweeping panorama of violence, revolution and covenant, get a strong cup of coffee and a hard back chair.

There was a time, the story goes, when if a local collided with a drug trafficker’s car on the streets of Culiacán — a bastion of the infamous Sinaloa cartel — the narco was likely to hop out to check that everything was ok.

“They’d say: ‘If you have any problems call this doctor and I’ll pay,'” says journalist Javier Valdez, who specializes in delving into the entrails of drug trafficking culture in Sinaloa. “Not anymore. Now they’ll get out of the car with a pistol. Not only will they not pay you; they’ll beat you, threaten you, or kill you.”

Such tales of shifting mafia etiquette are part of the legend of the underworld in Sinaloa but, close observers like Valdez say, there is also truth to the idea that the newer generations rising up within the Sinaloa drug trafficking scene are more violent and impulsive. And none more so than the one emerging to take control right now.

Few in Culiacán dispute Chapo’s status as a ruthless and bloodthirsty operator, but many credit his generation of Sinaloa traffickers with ensuring the cartel is still considered less wholeheartedly exploitative and sadistic than some other Mexican groups, such as the Knights Templar or the Zetas. While the point is often overstated, the Sinaloa cartel leadership has traditionally limited the expansion of side-rackets, such as extortion and kidnapping, at least on its home turf.

[ … ]

At other times the cartel has prospered because Chapo and his peers have maintained strong relationships with the impoverished communities where they grew up, Valdez says. The writer also emphasized that such leaders have often shown themselves to be been smart enough to know when to negotiate with enemies, including rival cartels, politicians, state security forces, and even the Drug Enforcement Administration, or DEA. This may not be the case, he says, with their more impetuous offspring.

“This generation does not have this sense of belonging, they’re more violent, more dangerous,” Valdez warns. “Their ascendency could put the stability of the cartel at risk.”

Those fears have proven true enough, as the current cadre of Hispanic and Latino crime lords have been known to behead, torture, and engage in inflicting pain and violence merely for the pleasure they see in it with no intended tactical advantage. I have long said that I don’t believe in the war on drugs, but that without such a misinformed and misdirected campaign the cartels would still exist because they are warlords and shouldn’t be considered “drug” cartels per se. Just as the Tehrik-e-Taliban engage in extortion, kidnapping, and mining of precious metals and gemstones, the Hispanic and Latino cartels aren’t restricted to drugs.

They have expanded into timber harvesting, and this has caused enough problems in one area of Mexico to catalyze the violent overthrow of the government and cartels altogether.

CHERÁN, MEXICO — Silently in the mountainous deep green of southwestern Mexico’s ancient pine and oak forests, volunteers armed with automatic weapons press forward on patrol.

They aren’t hunting insurgents or drug smugglers, common here in Michoacan state. And they aren’t part of any army. These self-appointed guardabosques — forest guards — are defending the land from illegal clear-cutting by regional organized crime cartels.

In doing so, they illustrate a determination not to succumb to despair in the face of violence — a commitment Pope Francis urged on Mexicans during a visit to Michoacan earlier this month.

Few people interviewed here last year would give their full names out of concern over retaliation. But they were undeterred nonetheless. Jacinto, from a neighboring village, explained what happened: “The trouble began in 2008. That’s when the federal officials came in with the gun registry lists and went house to house. They took our guns away.”

That disarmament effort, to which locals ascribe to nefarious motives, left them with only antiquated single-shot weapons for hunting vermin. These were of little use when the cartel loggers came over the mountain in 2010.

In his cowboy hat and black-and-white plaid shirt, Don Santiago, a 62-year-old wiry, soft-spoken resin farmer of the Purhépecha tribe, said organized criminal syndicates have entered into the large-scale forest destruction business. “We couldn’t go to the police,” he said. “The police were in the pay of the gangsters.”

The main criminal cartels in Michoacán are known as The Michoacán Family, known as La Familia for short, and the Knights Templars, or Templares.

Tension rose as the people of Cherán found their treasured forests being leveled closer to home. Huge, noisy lumber trucks tore through town to haul out the logs, seemingly around the clock. With police and elected officials unwilling to help, a small group of local women, led by a diminutive, five-foot firebrand affectionately known as Doña Chepa, rose up to take their forests back.

“The breaking point came on April 15, 2011,” said David, a big, animated Purhépecha tribesman. “It was Holy Week. The women came to stop the clear-cutters.”

About 15 women piled rocks on the roads as barricades. With the trucks immobilized, the women used rocks and fireworks to chase the cartel raiders away. A church bell clanged an alarm for citizen reinforcements. When the police arrived, the women directed their fireworks on them, pushing them back. “We surrounded all the exits to the town,” David said.

Nothing like this had happened before in Cherán. Energized locals directed their rage at the politicians who had done nothing to stop the deforestation. Armed with their obsolete hunting rifles and shotguns, families converged on the town center. Using one of the abandoned logging trucks as a battering ram, citizens stormed the town administration building and police station and overthrew the local government. The police abandoned their posts — and their weapons.

Mexico’s militarized police, even in small towns, often carry AR-15 assault rifles. Now those weapons were in the hands of the townspeople. “Then we started the rondas,” David said, referring to the armed citizen patrols.

The townspeople created a provisional government and banned political parties so that no candidate for public office would be beholden to outside political forces. They invented an electoral system to eliminate vote-buying and ballot-stuffing. All candidates for public office had to stand in the central square, with their supporters lining up behind them to determine who would win. Gangsters sent agents into the villages to burn cars and homes, and hunt down the guardabosques. In the course of the next three years, 18 of Cherán’s defenders, including Don Santiago’s brother, would be killed, and five more disappeared before the organized crime operations were shut down.

Cherán is a tidy little town that’s closed to outsiders. Heavily armed uniformed guards man checkpoints at every entrance and exit, questioning people whose faces or vehicles they don’t know. Hand-painted graffiti, in neat lettering, tells outsiders what the locals really think: “Leave us alone.”

To save face while recognizing reality, the Mexican government officially accepted Cherán’s new autonomous status. It deputized the checkpoint guards and guardabosques as the de facto authority to protect the forest lands. It issued them uniforms as “community police,” without attempting to take away or even register their newfound automatic weapons.

Federal police in shiny black twin-cab pickup trucks, wearing black tactical gear and armed with M4s and an occasional roll-bar-mounted machine gun, patrol the clean superhighways and the potholed back roads of rural Michoacán. The locals generally welcome the federales, sent in last year by President Enrique Peña Nieto to crush the cartels. The federales don’t interfere with Cherán’s guardabosques, and keep in contact with them by radio.

The checkpoint guards, young men in their late teens or early 20s, wear blue uniforms bearing embroidered seven-point stars and custom-made shoulder patches.

This is truly great investigative reporting, the kind we don’t often see any more. I applaud the folks in this little corner of the world. But will it last, and can it expand?

The article concludes with this. “Our whole way of life is in these forests,” said Don Santiago, the soft-spoken tribal elder. Tapping the resin from highland pines is a way of life, and an art, he inherited from ancestors who can be traced back to the Aztec empire. An individual pine tree can be tapped for up to 80 years for resin sold as raw material for industrial and food products. “The pines have faces,” said Don Santiago, reflecting the mysticism of his people.”

Their way of life is tied up in the forest and protecting it’s health and viability. But what if instead of cartel violence, they employ another strategy? What if they get to several of the mothers and tell them, “We’re here to help you. Here is a million dollars for each of you, take your family across the border, enroll you children in American schools and universities, and live a much better life than you could here?” Will they break, or are they committed to a world view that can sustain them against the advances of their enemies, come what may?

At WRSA there is a salient question being posed concerning the American constitution and body of constitutional law. It isn’t worth a duck’s fart, concludes the analysis, because it admits to, among other things, abortion on demand. True enough, abortion is murder against the innocent, and whether you are a conservative Christian like me, or a committed libertarian (in which case abortion is unjustified aggression against an innocent party), a country that sacrifices its young won’t long last as a viable entity.

I’ll give you the premise of the article, as long as you give me the following stipulations. The American constitution is the best that man has come up with so far, by a long ways, as long as you consider what John Adams said about it. “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

Implemented by gargoyles, demons and bloodthirsty tyrants, the constitution is like the Book of Church Order for Presbyterians. It becomes merely a system of protection of those in charge, regardless of what those in charge do. It can be twisted to say anything you want as long as you see the world through the eyes of evil. And thus we are back to world and life views.

My own views on this are fairly well known, and I have rehearsed them before. The views of my teacher, John Calvin, are the very basis of the American war of independence. Douglas Kelly, my former Systematic Theology Professor (along with C. Gregg Singer), observes the following.

Their experience in Presbyterian polity – with its doctrine of the headship of Christ over the church, the two-powers doctrine giving the church and state equal standing (so that the church’s power is not seen as flowing from the state), and the consequent right of the people to civil resistance in accordance with higher divine law – was a major ingredient in the development of the American approach to church-state relations and the underlying questions of law, authority, order and rights.

[ … ]

It was largely from the congregation polity of these New England puritans that there came the American concept and practice of government by covenant – that is to say: constitutional structure, limited by divine law and based on the consent of the people, with a lasting right in the people to resist tyranny.

When the rulers break covenant, as they did in the case above in Mexico, and as the King did against Americans, revolution is not only just, it is covenantally necessary. Covenant, to be proper, has two parts: promises and curses, the later applied for breaking covenant. These beliefs for me are, to use the words of philosopher Alvin Pantinga, incorrigible. There is never a time when I will not believe these propositions. Similarly, I don’t care one iota about the second amendment. As I’ve explained before, my rights are issued by divine decree, not a piece of parchment.

I have come by these beliefs the hard way. And I am concerned that the bases we claim for our liberties is founded in chaos, anarchy and whatever seems to be popular that particular day. But these things will not sustain you and your family in difficult times. Anarchy is the mother of tyranny because you aren’t the baddest person around. There is always somebody badder than you are. Into the void will always step a ruler more despotic than the last one. Ideas that float away with the wind will tire and disappoint you.

The most significant revolutions in the history of Western civilization are the reformation and the American revolution, both of which have their basis in the protestant reformation (and Calvinian theology). The Brothers of the Common Life taught the reformers everything – Luther was their student, and Calvin was deeply influenced by them. These men taught the reformers logic, letters, languages, mathematics, and everything else they needed to develop a coherent and powerful world view.

The reformation didn’t proceed and finalize without bloodshed, and lots of it. Swords were necessary, but the most important part was a world view that sustained the generations who fought this conflict on the European continent and on the British Ilse. Similarly, the men who founded this nation believed things that sustained them and their families in spite of the horrible losses they suffered.

I am an educated man. I hold an engineering degree – albeit Bachelor’s degree – from Clemson University. Clemson isn’t among the top tier schools like RPI or Cal Tech (which is unquestionably the toughest engineering and physics school in the nation), but it’s up there with NC State, Georgia Tech, Ohio State, University of Texas, and so on. I know fluid mechanics, strength of materials, statics and dynamics, differential equations, and so on. And I’ve had all of their stupid liberal arts courses, from their revisionist history classes to the English course where the professor couldn’t go a single class without sexual innuendo or double entendre. Oh, and don’t leave out that ridiculous sociology course where we studied everything from prostitution to poverty, all along the way rejecting the student’s demands that we solve these “problems” because we were just studying them, only to get to the issue of race in America with the professor starting the class that day with “How are we going to solve this problem?” When I brought up the logical inconsistency with the class heretofore, I was savaged by the other students for being a prejudiced bigot. A bigot I’m not, a lover of consistency I am.

If you think this is a discussion on how smart I am, you have it all backwards. In my opinion I left college a dullard and ignoramus. My real education began in graduate level seminary under Dr. C Gregg Singer, who assigned reading in Francis Turretin, “Institutes of Elenctic Theology.” I was left on my own with Turretin to self-instruct, as with all graduate level courses. It was my first introduction to the so-called scholastic writers. I was overwhelmed and dumbfounded.

Reading through these volumes required lots of coffee, a hard back chair, and lots of time. I got such severe headaches trying to study these volumes that it made my stomach upset. I usually couldn’t get more than one or two sentences without having to stop and rehearse what I had read, how it related to the sentence before it, and ensure that I understood his points. When I shared my experience with my colleagues, they had the same experiences I did with Turretin. Mine wasn’t unique.

Horrace Mann has done his job well, yes? I only home schooled my children their final years in High School (I wasted money on Christian education for much of their previous years), and I wish I had home schooled all four of them all twelve years. The dumbing of the American child has been virtually complete, and combined with common core, the product of the public school system will be truly atrocious (and culpable to be manipulated). At another time I will share a horrible school experience with one of my sons, but that is saved for later.

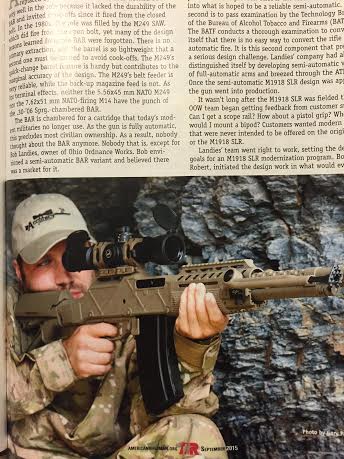

By all means, have your AR-15s. Get your comms gear and learn how to use it. I don’t begrudge learning how to conduct small unit combat maneuver warfare, patrolling techniques, perhaps satellite patrolling, make and break contact drills, carbine and handgun target acquisition drills, and so on. I’m not sure that it will be used, but I am certain that any future conflict will be fought in the shadows (more on that later).

But more than AR-15s with optics, good handguns and lots of ammunition and comms gear, you need a world view. You need an ideology that will sustain you through thick and thin, through life and until death. I cannot tell you how to craft yours. Most readers get annoyed or offended when I try to do that. I know mine – it is incorrigible. There are worse things than death. I will meet God face to face one day, and death doesn’t mean that my body cools to ambient temperature and that’s the end. I have been predistined to whatever God commands, and my life and death are in his hands. Thus shall my world view honor Him and remain unchanged by the winds opinion.

What about your world and life view?

Prior: I Do Not Fear Terror Because I Am Redeemed, And I Have Been Predistined To This War