Tom Nichols writing at L.A. Times:

Every disaster brings out human irrationality. When there’s a plane crash, we fear flying; when a rare disease emerges, we fear we will be infected. And when there’s a mass shooting in a church, we think we should bring more guns into churches. Or at least some people think so. This is a completely irrational response to the tragedy in Texas this week, but it’s being pushed by people for whom “more guns” is always the right answer to gun violence.

Sometimes, “more guns” is in fact the right answer. I am a conservative and a defender of the 2nd Amendment right to own weapons, and there are no doubt cases in which citizens who live and work in dangerous areas can make themselves safer through responsible gun ownership.

Packing in church, however, is not one of those cases. Despite wall-to-wall media coverage, mass shooting incidents are extremely rare: You are highly unlikely to die in one. Besides, civilians who think they’re going to be saviors at the next church shooting are more likely to get in the way of trained law enforcement personnel than they are to be of any help as a backup posse.

The “guns everywhere” reaction exposes two of the most pernicious maladies in modern America that undermine the making of sensible laws and policies: narcissism, and a general incompetence in assessing risk.

[ … ]

But even most well-intentioned people have no real sense of risk. They are plagued by the problem of “innumeracy,” as the mathematician John Allen Paulos memorably called it, which causes them to ignore or misunderstand statistical probabilities. They fear things like nuclear meltdowns and terrorist attacks and yet have no compunctions about texting while driving, engaging in risky sex, or, for that matter, jumping into swimming pools (which have killed a lot more people than terrorists).

[ … ]

Every action we take to protect ourselves involves some assessment of risk, and the uncomfortable truth is that there is very little people can do to prevent an attack from a lunatic or a terrorist. The good news is that most people — in fact, nearly everyone reading this right now — will never have to deal with those problems.

The desire to bring guns to churches is not about rights, but about risk. You have the right to carry a gun. But should you? If the main reason you’re holstering up in the morning is because it’s a family tradition where you live, or because you have a particular need to do so, or merely because you feel better with a gun, that is your right. But if you are doing so because you think you’re in danger from the next mass shooting, then you should ask yourself whether you’re nearly as capable, trained and judicious as you think you are — and why you are spending your days, including your day of worship — obsessing over one of the least likely things that could happen to you.

Incompetency in assessing risk is something displayed in the very article Nichols wrote, but more on that in a minute.

It’s amusing and even sad that he brought up the shooting in Walmart in Denver. We’ve already discussed that, and in no way, shape or form did anyone interfere with anything except causing the need for the police to watch a few additional hours of video. It’s as ridiculous to say that self defense is interfering as it was to say that the open carrier during the Dallas shooting caused police response to be delayed or impeded. It did no such thing, as the Dallas Police Department chased the actual perpetrator until the end. No one on scene was confused or misdirected – it was only cops watching videos hours after the event who were temporarily confused, and that was their own fault, not that of the open carrier.

Now back to the issue of risk. Nichols conflates the concept of probability and risk. They most certainly are not the same thing. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission explains risk as a product of probability and consequences, and this is usually determined using fault trees and Boolean Logic. Sophomoric explanations where the likelihood of occurrence of an event is equated with risk are not helpful, and certainly don’t rise to the level of good engineering.

Similarly, the food and agricultural industries use the same model for risk. Risk is the product of probability and consequences. An event can be a high likelihood and yet low consequences, and involve moderate to high risk, depending upon the magnitude of the consequences. An event can involve low likelihood and low consequences, and thus low risk. See the risk matrix linked above.

In my line of work, we have argued upon being backfitted or told to implement some set of modifications that the risk is low. When we argue in this manner we’ve always done our homework to substantiate those claims. At times we’re told to implement those modifications anyway because of public perception. But we never implement modifications without informing everyone of the cost. For example, “Implementing that set of modifications and backfits will cost $600 million.” Since we don’t grow money on trees, someone will pay for all of it. The cost doesn’t disappear – it will be borne by someone.

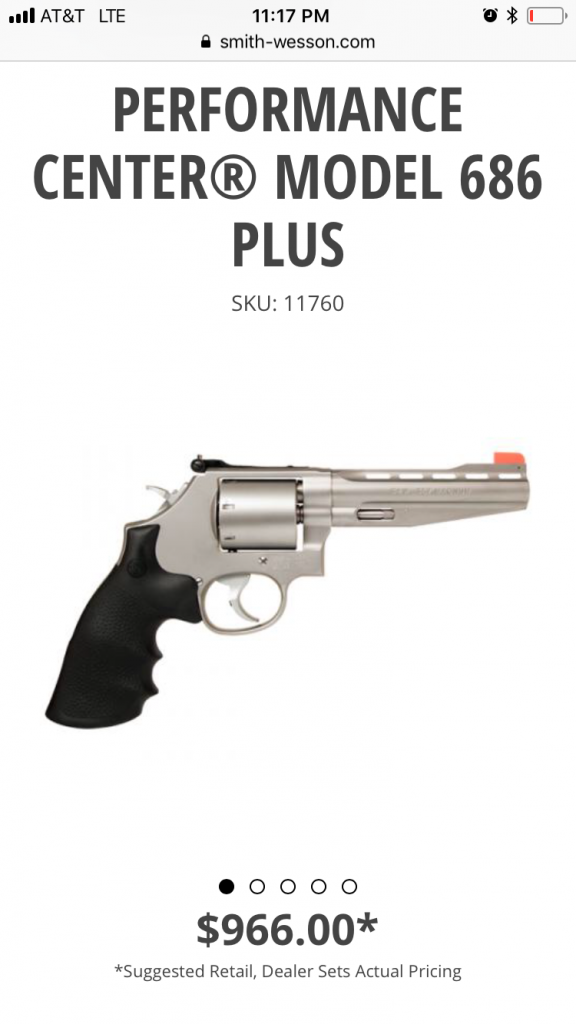

In the case Nichols discusses above, i.e., carrying a weapon to a worship service, it might have been moderately more compelling if he had argued that probability of the event is low, consequences are low, thus risk is low, and besides, the cost is extremely high (e.g., weapons cost $100,000 each). You always assess risk in terms of cost because if everything is free then there is no practical limit to the reduction of risk.

In his case he has argued for nothing. He has argued that he believes risk to be low (while conflating probability with risk), and thus carrying to worship is apparently a bad thing (while ignoring the high consequences of said event). But he hasn’t assessed the cost of this choice. For gun owners and carriers such as myself and many of my readers, there is minimal cost to this endeavor. Allow me to convey my personal observations.

I hate carrying things on my body. I don’t wear jewelry (rings, etc.), watches, or anything else that weighs me down. I even hate to carry a phone in my pocket. So when I made the decision to carry a number of years ago, it had to become a discipline or else it wouldn’t obtain. I had to consciously practice and rehearse the rules of gun safety, look for good belt support and holsters, spend time at the range, and on and on the carousel goes. Many readers can identify with my travails.

Over time it becomes habit such that conducting yourself in a safe and efficient manner becomes second nature. Now let’s suppose that I spend my whole life attending worship services carrying a weapon and no such awful event ever occurs. I hope this is indeed the case. If so, then I have lost nothing. The cost to me has been minimal (the cost of a good firearm), and the time spend developing self discipline. On the other hand, I have been prepared for an event of unknown probability but high consequence, with at least moderate and perhaps high risk.

It makes perfect sense to conduct myself in this manner. But the strained argument Nichols put forward offers no compelling reason to adopt his approach. One gains absolutely nothing by following his counsel, and you stand to lose big due to moderate to high risk.

Nichols is a professor at the Naval War College. This makes the third article within one week from persons within the defense apparatus – or loosely affiliated with the defense apparatus – taking a gun controller viewpoint. First it was Adam Routh with CNAS hyperventilating about North Korea getting night vision equipment (so we needed to put it on the prohibited list for American civilians).

Next, Phillip Carter weighed in with this formal fallacy: (1) Pistols are ineffective against vehicular attacks, (2) Vehicular attacks is terrorism, therefore, (3) Pistols are ineffective against terrorism. It’s almost as if someone makes the call to the next Kamikaze pilot: “You’re next. It doesn’t matter how stupid you look or how bad your case is, it’s your turn to be the controller of the day.”

Who does this? Everytown? Former president Obama? Who makes these calls, and how does this go down? There must be some sort of outside pressure to do this sort of thing in order to go public with such a knuckleheaded commentary as this.

We may never know, but for the future, Mr. Nichols, research your concepts, be precise in your definitions, and be a critic of your own work before it goes out in order to find and fix its weaknesses. Obviously, the editors aren’t going to do it.