Review and Analysis of the Afghanistan Campaign

BY Herschel SmithMajor General Charles Dunlap, Jr., defends the heavy use of air power in Operation Enduring Freedom.

“Tanks and armor are not a big deal — the planes are the killers. I can handle everything but the jet fighters.” This recent conversation between Taliban commanders, intercepted by U.S. intelligence officers, does much to explain the frenzied efforts of their propaganda machine to ban the use of the weapon they fear most: airpower …

What is frustrating them? Modern U.S. and coalition airpower. Relentless aerial surveillance and highly precise bombing turn Taliban efforts to overrun the detachments into crushing defeats. And the Taliban have virtually no weapons to stop our planes.

Instead, they are trying to use sophisticated propaganda techniques to create a political crisis that will shoot down the use of airpower as effectively as any anti-aircraft gun.

Indeed, it may have been the very heavy use of air power thus far which has prevented total loss of the campaign given the underresourced effort (with respect to infantry), but while air power can participate heavily and even prevent the loss of the campaign in this case, it cannot win. Troops on the ground must accomplish that task, even if they utilize air power to assist them.

The Captain’s Journal has called for more troops in the campaign, stating that the recent addition of a few thousand troops will not be nearly enough (and General McKiernan agrees with this assessment). But contrary to our position, Fred Kaplan weighs in on why he believes that a surge will not work in Afghanistan.

… the situation in Iraq bears little resemblance to that of Afghanistan. Barnett Rubin, a professor at New York University and author of several books about the country, spells out some of the differences:

Iraq’s insurgency is based in Iraq; Afghanistan’s Taliban insurgents are based mainly across the border in Pakistan. Iraq is urban, educated, and has great wealth, at least potentially, in its oil supplies; Afghanistan is rural, largely illiterate, and ranks as one of the world’s five poorest countries. Iraq has some history as a cohesive nation (albeit as the result of a minority ruling sect oppressing the majority); Afghanistan never has and, given its geography, perhaps never will.

Moreover, the Taliban’s insurgency is ideological, not ethno-sectarian (except incidentally). Therefore, while some warlords and tribes have allied themselves with the Taliban for opportunistic or nationalistic reasons, and therefore might be peeled away and co-opted, the conditions are not ripe for some sort of Taliban or Pashtun “Awakening.” Nor is there any place where walls might isolate the insurgents.

Kaplan then tells us what he believes is possible for the campaign.

The ultimate military goal—one lesson from Petraeus’ strategy in Iraq that is worth learning and might be applicable—is to protect the Afghan population, and that requires putting a lot of troops in the neighborhoods of towns and villages, to provide security and build trust. It might be possible to do this in Afghanistan, just as it was done in many Iraqi neighborhoods with one important difference—it has to be done by the Afghan National Army, not by us.

There are a few reasons for this. First, we simply can’t do it. Stephen Biddle—a military analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations, who was an adviser on some aspects of Iraq strategy—estimates that securing the Afghan population would require about 500,000 troops. That’s 10 times the combined number of U.S. and NATO troops in Afghanistan now. We don’t have anywhere near this level of manpower to spare (the three extra U.S. brigades under consideration would amount to about 12,000 troops), and even if we did, and even if we wanted to send them, we’d have no way to maintain them. (In Iraq, Saddam Hussein left behind a robust logistical network, including paved highways and lots of air bases with long runways; Afghanistan has nothing of the sort.)

Second, unlike in Iraq—where sectarian clashes required U.S. troops to step in (Sunnis wouldn’t trust Shiite troops, and Shiites wouldn’t trust Sunni troops)—the Afghan army is seen as, and actually is, a national institution. Given the right resources, it could do the job … And that leads to something that we and other countries could do—pour lots and lots of money into Afghanistan, so the government can equip, train, and pay a much larger national army.

These are some pregnant paragraphs by Kaplan, and bear some unpacking to acertain both the wisdom and folly in them. Kaplan is right concerning the absence of an awakening of the sort that occurred in the Anbar Province. This is the subject of a debate we’ve had at the Small Wars Council, and we maintain our position that while a few insignificant Taliban may be able to be peeled away from the force, in the end it will have little if any effect on the effort. The ideological connection between the Taliban and al Qaeda that led to safe haven in Afghanistan prior to 9/11 remains, and rather than be introduced to the foreign notion of radical Islamic Sharia as did the Anbaris, the Taliban have no need of such an introduction.

So if the U.S. isn’t (and shouldn’t be) interested in forming another fledgling democracy in an otherwise strictly Islamic region, why should we care if they rule their people via Sharia? The answer comes not in Sharia, but in the symbiotic connection between the Taliban and al Qaeda we mentioned above, i.e., friendship with and support of globalists.

The Taliban of Afghanistan prior to 9/11 were not so much focused on global jihad as was al Qaeda, but the seeds for the ideology were present enough for the Taliban to grant safe haven to al Qaeda. With the advent of the Tehrik-i-Taliban of Pakistan (TTP), a new order has come about and the Taliban have clearly said that their focus is global. Terrorists are flooding in from around the world to be trained for global jihad in Baitullah Mehsud’s camps. The Tehrik-i-Taliban are hard core radicals, and shout to passersby in Khyber “We are Taliban! We are mujahedin! “We are al-Qaida!” There is no distinction.

In spite of the demand by the principles of counterinsurgency to build roads, schools, power grids and infrastructure, the population has clearly said that they demand security from the Taliban threat instead. The Anbar awakening occurred with indigenous, non-al Qaeda fighters who had no love for extremism. It didn’t occur with al Qaeda. To believe that an “awakening” can occur within the Taliban is analogous to faith that al Qaeda will turn against itself. They – al Qaeda and the Taliban – are one and the same.

Kaplan’s proposal that it will require half a million U.S. troops to provide security for the population of Afghanistan isn’t far off the mark set by Australian Major General Jim Molan.

International forces in Afghanistan are repeating mistakes made in Iraq by failing to commit sufficient troops, a recently retired Australian army general said Tuesday.

Maj. Gen. Jim Molan said he could see parallels between the worsening situation in Afghanistan and the months after the defeat of the Iraqi military when he commanded 300,000 troops in Iraq as Chief of Operations for the U.S.-led multinational force in 2004 and 2005.

“The biggest error that we made in the second year of the war in Iraq, 2004, was that we didn’t have unity of effort or command, and we didn’t have a comprehensive plan and we didn’t have sufficient troops,” Molan, who retired from the army this year, said in a lecture to a conservative think-tank.

“We are making exactly the same mistake now, and although none of us has done much, the Americans have moved in and solved the unity of effort by putting one of their people in command of everything,” he said of U.S. Gen. David D. McKiernan, who took over the NATO command in Afghanistan in June.

“There’s a chance now they’ll get a comprehensive plan up — it’s going to be difficult working with NATO … and I think we are years away from getting anything that approaches sufficient troops into Afghanistan,” he added.

Molan estimated about 500,000 troops were needed in Afghanistan, where there are currently 65,000 foreign troops and 62,000 Afghanistan National Army soldiers.

“The aim of the Taliban is to get into the cities and fight us like they’re fighting us in Iraq,” Mola said.

“Iraq is what Afghanistan will be if the Taliban get back into the cities and nothing will change,” he added.

Australia is the largest contributor to Afghanistan outside NATO. There are 1,000 Australian troops in the central Asian country.

Molan dismissed the Australian government’s argument that it did not have sufficient troops to send more.

“I believe we can afford to put more troops in and I believe we can afford to sustain them, but it would require governments to back that idea up,” Molan said.

But he said the onus was on NATO to commit the thousands of additional troops required to win the conflict.

Quite obviously the U.S. doesn’t have half a million troops to provide security for Afghanistan. Australia must change as well as the balance of NATO (regarding rules of engagement). Currently, Australia allows only its special forces to engage kinetic operations, and other Australian forces are limited to force protection—rigidly imposed to the point whereby participants have been required to sign formal documents declaring that they have not provoked combat operations.

But if NATO should do more, so should the U.S. whose generals have claimed that Operation Enduring Freedom is an underresourced campaign for several years. The Captain’s Journal has gone on record stating that the U.S. is losing the campaign because of degrading security. Following this article, Andrew Lubin wrote to tell us that:

The downside of “getting the word out” is that lots of people don’t like to read it. You wrote a good piece (and have always done so); and I hope you will continue. Did you see yesterday’s lead editorial in the NY Times “Afghanistan on Fire”…you need to read it. I spent June over there; it’s worse than you can imagine; it’s like Iraq in 2004-2005.

Now Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic & International Studies has written a comprehensive report entitled Losing the Afghan-Pakistan War?: The Rising Threat. In this analysis Cordesman concludes that the Taliban have turned much of Afghanistan into “no-go zones.”

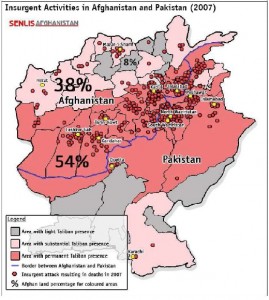

The map above shows insurgent activities in 2007, and the rate of attacks in 2008 has been higher than in 2007. The darker red indicates the areas with permanent Taliban presence. The “border” between Afghanistan and Pakistan effectively doesn’t exist.

The erstwhile capital city of the Taliban, Kandahar, is in obvious need of protection against the thugery and oppression by the Taliban.

The neat rows of new homes in the gated community sit behind freshly painted three-metre-high cement walls and rows of manicured shrubs.

Pavements lined with imported eucalyptus trees border smoothly paved streets that fill at twilight with cyclists and walkers. Further back, another cluster of houses is being built, including an eight-bedroom villa with a pool, wraparound deck and balcony supported by doric columns.

Residents at the Aino Mina housing development also have access to a mosque, two private schools, football fields, playgrounds and private armed guards on duty 24 hours a day. A hospital, supermarket, pizza parlour and golf course are also planned.

But, despite luxuries rivalling those found in exclusive suburban communities in the United States, many owners are trying to sell or rent out their homes. Others have temporarily abandoned properties. The reason is as simple as the long-standing estate agent’s maxim: location, location, location.

This upmarket residential neighbourhood is situated on the outskirts of the provincial capital of Kandahar – one of the most volatile and lawless provinces of Afghanistan. Others call the area the heartbeat of the Taliban, the place where the group formed in the early 1990s and where it is, by all accounts, re-establishing itself today.

“I’m leaving tomorrow,” Sayed Hakim Kallmi, a 40-year-old hotel manager, said as he stood on the pavement outside his dream home in Aino Mina. He was watching his son and three of his six daughters play with neighbours. “There’s no security here” …

Taliban operatives have made no secret of their campaign to intimidate residents of Aino Mina. Ahmadi, who described himself as a spokesman for the group, said: “We seriously warn people not to buy here. Those who stay there and who buy there will be held responsible for the actions we take against them later.”

Residents and workers in the development say the Taliban have targeted the area and maintain an unmistakable presence. During a sweltering July afternoon, a thickly bearded man in a shalwar kameez with a turban wrapped around his head rode a motorcycle along the nearly empty streets of Aino Mina with an AK-47 strapped across his back. The motorbike and the AK-47 both are long-favoured hallmarks of the Taliban.

Despite the rider, a handful of construction workers at the project hauled wheelbarrows full of dirt, lugged slabs of concrete and scaled bamboo ladders. Naik Mohammed, 28, pointed to a two-story townhouse and said Taliban militants had recently looted the elegant dwelling and demanded protection money from its occupants.

“They told the owners to pay $200,000 and they would allow them to live there peacefully and they won’t kill them,” Mohammed said. “The family left the next day.”

Admiral Mullen himself – Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff – has said that time is running out on Afghanistan. The push to treat the campaign against the Taliban as a counterterrorism operation against so-called high value targets with limited force presence and small footprint has enabled Taliban control of the human terrain. The fact that neither the U.S. nor NATO has 500,000 troops to dedicate to Operation Enduring Freedom is not an excuse for continued failure to ramp up troop presence to capture and kill Taliban and train Afghan troops to do the same.

The objection that the U.S. cannot contribute 500,000 troops must be placed in context. There are currently just over 32,000 troops in Afghanistan, somewhere around one fifth of the forces in Iraq. Before the defeatists howl that the campaign cannot be won, it is prudent to take the campaign seriously and listen to the Generals when they declare it to be an underresourced campaign.

The battle of wanat where nine U.S. soldiers were killed and fifteen wounded is indicative of more than just that the Taliban can conduct larger scale operations when they desire. No Afghan troops died in the engagement, since the U.S. forces took the brunt of the punishment. It will be protracted period of time before Afghan troops can be relied upon perform kinetic operations sufficiently enough to push back Taliban presence in Afghanistan without significant U.S. force projection.

Further, religiously motivated fighters (jihadists and globalists) and thugs and criminals who extort thousands of dollars from the population must be captured or killed. We can no more reconcile with these elements than we did with al Qaeda in Anbar. While al Qaeda attacked and brutalized the Anbaris, the indigenous insurgents for the most part did not. Their attacks were reserved for U.S. forces until being killed or captured to the point that their ranks were decimated by U.S. Marines, the rest being co-opted by U.S. dollars and protection. Al Qaeda was never offered dollars for reconciliation. They were simply killed. Concerning reconciliation with an insurgency, it is important to get this distinction correct.

Other Resources:

A Wild Frontier (The Economist): Yet a devious Pakistani strategy of failing to crack down on cross-border violence is not the only reason it persists, nor the main one. A better explanation, given the fraught, radicalised and ungoverned state of north-western Pakistan, and the many dead soldiers there, is that the army could not make a much better fist of controlling the border, even if it did its damnedest. And moreover, it may be afraid to pursue its campaign more vigorously, for two reasons. Pakistani officials suggest that, despite battling the Pakistani Taliban in the tribal areas, the army is reluctant to attack the Afghan Taliban, allegedly led from Peshawar and from Quetta, capital of Baluchistan province, for fear of worsening security problems in those places. Secondly, the campaign is unpopular, in the army and elsewhere, precisely because Pakistanis think it is being waged for America.

A Modernized Taliban Thrives in Afghanistan (Washington Post) : Just one year ago, the Taliban insurgency was a furtive, loosely organized guerrilla force that carried out hit-and-run ambushes, burned empty schools, left warning letters at night and concentrated attacks in the southern rural regions of its ethnic and religious heartland. Today it is a larger, better armed and more confident militia, capable of mounting sustained military assaults. Its forces operate in virtually every province and control many districts in areas ringing the capital. Its fighters have bombed embassies and prisons, nearly assassinated the president, executed foreign aid workers and hanged or beheaded dozens of Afghans. The new Taliban movement has created a parallel government structure that includes defense and finance councils and appoints judges and officials in some areas. It offers cash to recruits and presents letters of introduction to local leaders. It operates Web sites and a 24-hour propaganda apparatus that spins every military incident faster than Afghan and Western officials can manage

U.S. Seeks Sweeping Changes in Command Structure for Afghanistan (The Captain’s Journal): Without drastic changes in the nature of the mission of NATO troops, it is doubtful that even placing them under the command of General Petraeus will change much. This is partly why we have recommended more U.S. troops. Petraeus must have access to resources that will operate with regard to unity of command, unity of strategy and unity of mission. Time is short in the campaign, Pakistan’s intentions cannot be trusted, and the security situation is degrading.

Fighting a Technologically Advanced Insurgency (The Captain’s Journal): Both the U.S. DoD and the British MoD should invest as necessary to stay ahead in technology. But we must not miss the point concerning technology. Playing the game of one-step-ahead is a deadly and costly way to run a campaign. The solution to the problem of Taliban technology is to conduct intelligence driven raids against the Taliban who perpetrate the use of such technology. Rather than the so-called high value targets with recognizable names, the real high value targets are the Taliban perpetrators, the fighters, technicians and practitioners.

The Cult of Special Forces (The Captain’s Journal): But the advent of each new story about SOF that kills some high profile name, while riveting for the non-military reader, continues the same lesson that Rumsfeld took into Afghanistan with his vision of airmen with satellite uplinks guiding JDAMS to target, CIA operatives, and alliances with rogues in the country who could knock out the Taliban. Afghanistan is a failing campaign precisely because of this view. Counterinsurgency requires infantry and force projection, those things necessary to ensure security for the population.

Interview with Taliban Spokesman Maulvi Omar (The Captain’s Journal):

Q: What is the difference between al Qaeda and the Taliban? Have they any relation?

A: There is no difference. The formation of the Taliban and al Qaeda was based on an ideology. Today, Taliban and al Qaeda have become an ideology. Whoever works in these organizations, they fight against kafir (infidel) cruelty. Both are fighting for the supremacy of Allah and his Kalma. However, those fighting in foreign countries are called al Qaeda, while those fighting in Afghanistan and Pakistan are called Taliban. In fact, both are the name of one ideology. The aim and objectives of both the organizations are the same.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post. TrackBack URL

Leave a comment