Obama Administration Searching for an Exit Strategy in Afghanistan

BY Herschel SmithRaising expectations for scaling back military operations in Afghanistan, President Barack Obama said Tuesday he hopes U.S. involvement can “transition to a different phase” after this summer’s Afghan elections.

The president said he is looking for an exit strategy where the Afghan security forces, courts and government take more responsibility for the country’s security. That would enable U.S. and other international military forces to play a smaller role.

Obama made his remarks after an Oval Office meeting with Dutch Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende. Talks between the two leaders included discussion of the Netherlands’ help with the U.S.-led effort to defeat Taliban and al-Qaida forces in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Dutch combat troops have been a mainstay among the allied forces fighting in the volatile southern reaches of Afghanistan.

After taking office in January, Obama reviewed U.S. progress in Afghanistan and announced in March a new approach that included sending an additional 17,000 combat troops, including Marines who have just kicked off an offensive in Taliban strongholds in the south of the country …

In remarks in Moscow last week, Obama said it was too early to judge the success of his new approach in Afghanistan because “we have just begun” to implement it. Obama also installed a new U.S. ambassador, Karl Eikenberry, in May and a new U.S. military commander, Gen. Stanley McChrystal, in June.

On Tuesday, however, the president emphasized an exit strategy.

“All of us want to see an effective exit strategy where increasingly the Afghan army, Afghan police, Afghan courts, Afghan government are taking more responsibility for their own security,” he said.

If the Afghan presidential election scheduled for Aug. 20 comes off successfully, and if the U.S. and its coalition partners continue training Afghan security forces and take a more effective approach to economic development, “then my hope is that we will be able to begin transitioning into a different phase in Afghanistan,” Obama said.

Analysis & Commentary

This is a remarkable report for one particular point we learn about this administration’s view of Operation Enduring Freedom. But before we get to that point, let’s pause to reflect on the context.

Operation Iraqi Freedom proved to be much more difficult that we originally thought it would be for a whole host of reasons. There have been many lessons (re)learned about counterinsurgency and nation-building, including the need for national and institutional patience. It takes a long time and is costly in both wealth and blood. There is a never-ending need for highly functional lines of logistics, and the chances of an acceptable outcome is (at least in the early and even middle stages) proportional to the force projection, one factor of which is the troop levels. We have relearned that it is very difficult to rely on Arabic armies in large part because of corruption, incompetence and the lack of a Non-Commissioned Officer corps that is equivalent to the NCO corps in the U.S. armed forces. It has been documented that this has directly affected the degree of success of the efforts to build an Iraqi Army.

For reasons of difficulty and cost, many believe that the U.S. should not engage in counterinsurgency and nation-building. As the argument goes, when an existential threat is judged to exist, forcible entry is conducted, the regime is toppled, and U.S. forces leave to let the population sort out the balance of its history. If this threat returns or another is perceived, then do it all over again. While the cost of this approach is likely to be greater in the long run (in our estimation), there are a great many who hold this view, even among field grade and staff level officers (based our own on communications).

But when a counterinsurgency campaign is begun, not only does the doctrine say that it will be protracted, but this doctrine is exemplified by our experience in Iraq. While continually adjusting strategy and tactics to press forward to a conclusion is appropriate, it doesn’t work to assume that it will be easy or shortlived.

But there are differences in campaigns for which the doctrine must be maleable. As we have discussed before, General Petraeus has said that of the campaigns in the long war, Afghanistan would be the longest.

I did a week-long assessment in 2005 at (then Defense Secretary Donald) Rumsfeld’s request. Following our return, I told him that Afghanistan was going to be the longest campaign of what we then termed “the long war.” Having just been to Afghanistan a month or so ago, I think that that remains a valid assessment. Moreover, the trends have clearly been in the wrong direction.

This is true for numerous reasons, including the difficulty in logistics, lack of a strong central government, corruption, an increasingly problematic security situation, etc. If Hamid Karzai wins the election, the very head of the government in which the U.S. administration is placing its hope is the man who recently pardoned five heroin smugglers, at least one of them a relative of a man who heads Karzai’s campaign for re-election.

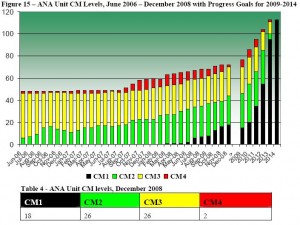

The administration’s plan falls heavily into the lap of the Afghan National Army. This is the same Army that is believed to have colluded with Taliban fighters to kill U.S. troops at the Battle of Bari Alai, and which, according to U.S. Marine embedded trainers, would lose as much as 85% of its troops if drug testing was implemented. Fully independent ANA Battalions are targeted, but this is many years down the road, in the year 2014 at the earliest. Even this may be wishful thinking.

It wouldn’t have been surprising if Obama had advocated complete withdrawal, although we would have disagreed with this decision. It wouldn’t have been surprising if he had advocated long term commitment, since this is the nature of counterinsurgency. When we pressed for the resignation of National Security Advisor Jim Jones, we noted that he had stated that the new strategy had the “potential to turn this thing around in reasonably short order.”

Nothing happens in counterinsurgency in short order, we observed, and thus his counsel to the President is poor. The Generals are indignant, and have retained the right in their mind to request the troops they believe to be necessary for the campaign. But this view has not been heard in Washington, and not only does Obama’s counselors and advisers believe that the campaign can be turned in short order, but we now learn that Obama believes this – contrary to doctrine, contrary to the views of General Petraeus, contrary to the Generals, and contrary to the lessons of Iraq. Everyone wants an exit from war. No one likes to see the human cost of battle. The question is not one of exit – it is of when and how?

While issues of life and death play themselves out in Afghanistan and sons of America continue to lose limbs and lives, the administration blythely continues to believe in myths and fairly tales concerning war and peace, and fashion plans for Afghanistan that have no chance to succeed. The plans must change, but until they do, the question is what the cost will be in national treasure and blood?

Prior Featured:

Calling on National Security Advisor James L. Jones to Resign

Marines Take the Fight to the Enemy in Now Zad