It’s Time to Engage the Caucasus Part II

BY Herschel SmithAfter discussing the recent disputations that have occurred between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Stephen Blank goes on to make recommendations for greater U.S. engagement in the Caucasus.

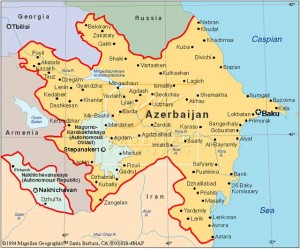

The U.S. has displayed indifference, or at least apathy, toward the situation. This needs to change. Armenia’s threats reflect the facts that NATO disregarded Armenia’s claims and that the OSCE, largely because of distrust between the U.S. and Russia, cannot bring itself to function as intended (i.e., as a mediator). But the threats also reflect the fact that behind most of the headlines, this has been a very good year for Azerbaijan in its international relations, particularly its energy diplomacy. As a result, Azerbaijan has become more strategically important to the West, including the U.S.

Baku has stood its ground with Moscow. While doubling gas exports to Russia, it signed a major deal with BP to develop new gas holdings off its shores, thus not only maintaining its energy independence, but also demonstrating the importance of the planned Nabucco pipeline to Europe. Azerbaijan has also visibly improved its relations with Turkmenistan, to the point where a Turkmen decision to send its gas to Europe through pipes traversing Azerbaijan is now quite conceivable. Further, Azerbaijan signed a four-party deal to build an Interconnector that will send Azeri gas through Georgia and the Black Sea en route to Romania and then Hungary. This deal enhances Azerbaijan’s importance to Southeastern Europe as a reliable supplier of oil and gas. Also in 2010, Azerbaijan improved its ties and signed an energy agreement with Turkey.

While these agreements cannot hide the fact that no progress was made on Nagorno-Karabakh — over 30 serious incidents occur daily on the “Line of Contact” there — they do show Azerbaijan’s growing importance to Europe and self-confidence in international affairs. Armenia, by contrast, has little to show for its efforts except continuing dependence upon Russia. For example, because of its refusal to negotiate with Azerbaijan, Armenia remains estranged from Turkey — a situation that decreases Armenia’s GDP by 15 percent. Recent reports show that Armenia ran weapons to Iran, something that will hardly endear it to the West.

Blank goes on to describe the disaster that would be open war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and then concludes with this:

The 2008 Russo-Georgian War showed that even small wars in the Transcaucasus can have repercussions that far transcend the region. Failure to take an active role in resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh issue not only cements Armenia’s dependence upon Moscow and estrangement from Turkey and Europe; it also undermines the success Azerbaijan has had in strengthening Europe’s position vis-à-vis Russia on energy security. Continued neglect of Azerbaijan, and of the Transcaucasus as a whole, can only erode U.S. standing and damage its credibility in the region, confirming Russia’s belief that the reset policy amounts to an acknowledgement of its right to a sphere of influence over the Commonwealth of Independent States. Under the circumstances, the ongoing failure of the U.S. to play an active role here makes no sense at all — and worse, encourages the drift to war.

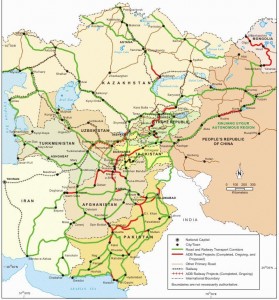

I had initially advocated engagement of the Caucasus region for at least two purposes, namely logistics (as an alternative to the troublesome line of logistics through the Khyber region or the increasingly troublesome Chamen area), and as a barrier to Russian assertion of influence in what it considers its “near abroad.”

Hidden, or perhaps simply assumed in my prose, was the understanding that the Caucasus region is oil and natural gas rich. Blank recognizes that the Caucasus is strategically important due not only to its oil and gas, but also as a potential way to blunt the force of Russian hegemony (or possible developing Russian hegemony).

So there are three good reasons to engage the Caucasus: (1) Oil and gas, (2) as a barrier to Russian influence (see Rapidly Collapsing U.S. Foreign Policy for as discussion of Russian basing rights and logistics in Armenia), and (3) as an already-proven line of logistics to Afghanistan in lieu of Pakistan. Actually, as Stephen Blank points out, in spite of the fear mongers who believe that Georgia will drag us into a war with Russia, there is a fourth good reason to engage the Caucasus region: to prevent war from occurring.

I don’t hold out high hopes that the Obama administration will pursue engagement of the Caucasus, as I am not convinced that they care about any of the above justifications that we have offered. However, Russia is not our friend, we still need logistics to Afghanistan, our automobiles and trucks still need to run in order to support our economy, and war between Armenia and Azerbaijan would be a humanitarian disaster.