From Greg Jaffe of The Washington Post:

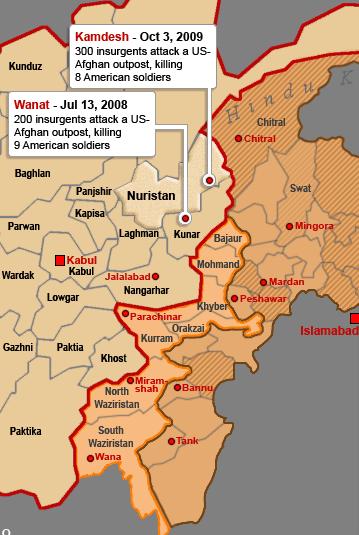

The Army’s official history of the battle of Wanat – one of the most intensely scrutinized engagements of the Afghan war – largely absolves top commanders of the deaths of nine U.S. soldiers and instead blames the confusing and unpredictable nature of war.

The history of the July 2008 battle was almost two years in the making and triggered a roiling debate at all levels of the Army about whether mid-level and senior battlefield commanders should be held accountable for mistakes made under the extreme duress of combat.

An initial draft of the Wanat history, which was obtained by The Washington Post and other media outlets in the summer of 2009, placed the preponderance of blame for the losses on the higher-level battalion and brigade commanders who oversaw the mission, saying they failed to provide the proper resources to the unit in Wanat.

The final history, released in recent weeks, drops many of the earlier conclusions and instead focuses on failures of lower-level commanders.

The battle of Wanat, which took place in a remote mountain village near the Pakistan border, produced four investigations and sidetracked the careers of several Army officers, whose promotions were either put on hold or canceled. The 230-page Army history is likely to be the military’s last word on the episode, and reflects a growing consensus within the ranks that the Army should be cautious in blaming battlefield commanders for failures in demanding wars such as the conflict in Afghanistan.

Family members of the deceased at Wanat reacted with anger and disappointment to the final version of the Army history.

“They blame the platoon-level leadership for all the mistakes at Wanat,” said retired Col. David Brostrom, whose son was killed in the fighting. “It blames my dead son. They really missed the point.”

The initial investigation, conducted by a three-star Marine Corps general and completed in the spring, found that the company and battalion commanders were “derelict in their duty” to provide proper oversight and resources to the soldiers fighting at Wanat.

Petraeus reviewed the findings and concluded that based on Army doctrine, the brigade commander, who was the senior U.S. officer in the area, also failed in his job. He recommended that all three officers be issued letters of reprimand, which would essentially end their careers.

After the officers appealed their reprimands, a senior Army general in the United States reversed the decision to punish the officers, formerly members of the the 173rd Airborne Brigade.

Gen. Charles Campbell told family members of the deceased that the letters of reprimand would have a chilling effect on other battlefield commanders, who often must make difficult decisions with limited information, according to a tape of his remarks. He also concluded that the deaths were not the direct result of the officers’ mistakes.

The Army’s final history of the Wanat battle largely echoes Campbell’s conclusions, citing the role of “uncertainty [as] a factor inseparable from any military operation.”

In its conclusions, the study maintains that U.S. commanders had a weak grasp of the area’s complicated politics, causing them to underestimate the hostility to a U.S. presence in Wanat.

“Within the valley communities there had been hundreds of years of intertribal and intercommunity conflict, magnified by hundreds of years of geographic isolation. Understanding the cultural antagonisms present in [Wanat] was difficult and complicated,” it said. “Coalition leaders had difficulty understanding the political situation.”

But the history focuses mostly on the failures of lower-level commanders to patrol aggressively in the area around Wanat as they were building their defenses. It also criticizes 1st Lt. Jonathan Brostrom, a 24-year-old platoon leader, for placing a key observation point in an area that did not provide the half-dozen U.S. soldiers placed there a broad enough view to spot the enemy.

“The placement of the OP [Observation Post] is perhaps the most important factor contributing to the course of the engagement at Wanat,” the report states.

The initial investigation, by contrast, found that the placement of the post was not a major factor in the outcome of the battle.

That investigation also found that mid-level Army officers failed to plan the operation beyond the first four days and as a result failed to provide sufficient manpower, water and other resources to defend the base from a Taliban attack. The official history makes little mention of such conclusions.

Analysis & Commentary

This information and perspective is mostly known to regular readers of The Captain’s Journal. We have discussed the Battle of Wanat many times before, and linked the final report as soon as it was released (as well as commented on the original Cubbison report).

The main theme of Jaffe’s analysis is the reversal of reprimands for senior staff level officers and the switch to holding lower level field grade officers accountable for the failures. But there are other aspects as well, and we must address those in order to crawl through the weeds. Unfortunately, the weeds block our view and add little to nothing to the overall reality of the situation.

One such weed garden is this notion that:

“Within the valley communities there had been hundreds of years of intertribal and intercommunity conflict, magnified by hundreds of years of geographic isolation. Understanding the cultural antagonisms present in [Wanat] was difficult and complicated,” it said. “Coalition leaders had difficulty understanding the political situation.”

Maybe true, maybe significant for other considerations, and maybe frustrating, but irrelevant in this context (the battle proper, and whom to hold accountable for what happened). It’s just weeds that block our view. In Analysis of the Battle of Wanat, we discussed how “The meetings with tribal and governmental officials to procure territory for VPB Wanat went on for about one year, and one elder privately said to U.S. Army officers that given the inherent appearance of tribal agreement with the outpost, it would be best if the Army simply constructed the base without interaction with the tribes. As it turns out, the protracted negotiations allowed AAF (anti-Afghan forces, in this case an acronym for Taliban, including some Tehrik-i-Taliban) to plan and stage a complex attack well in advance of turning the first shovel full of sand to fill HESCO barriers.”

Local intelligence, also from tribal elders, pointed to massing of forces and planned attacks on VPB Wanat. However complicated the tribal machinations and our attempts to understand them, they weren’t so complicated that we didn’t have good intelligence or even good counsel. Had we followed the elder’s advice, the patrol base might have been manned and fortified well before the massing of forces that occurred by the Taliban, and in fact local atmospherics might have been different with time for interaction with U.S. forces.

But if the notion of tribal complexities is a smoke screen, so is the issue of limitations in weapons capabilities. As we have discussed before:

It’s tempting to point the finger at weapons systems, just as it is tempting to fault the company with lack of soft COIN efforts. But in the end, they were outnumbered about 6:1 (300+ to about 50), they were on a poor choice of terrain, they had poor logistics, they suffered lack of air and artillery support, and most importantly, they simply were never given the proper number of troops or the resources to engage in force protection, much less robust force projection. They were under-resourced, and no analysis of weapons systems can change that fact. Rather than focus on why the M4 jams after firing 360 rounds in 30 minutes, the real question is why this particular M4 had to be put through this kind of test to begin with?

It’s wise to deploy the right weapons for the job, and if that means that each squad carries an M-14 for the DM position, then so be it. Commanding officers should make that happen. There are plenty of M-14s left in our armories, and they should be put to use in the longer distance engagements. But in the end weapons systems malfunctions is simply not a compelling excuse or even one of the root causes of what happened at Wanat. It just isn’t, and time spent on worrying over that is time wasted.

Col. David Brostrom is rightfully indignant over his son’s role in the report. Dead men cannot defend themselves, and Lt. Brostrom represents too easy of a target. In that respect, the final report is petty and cowardly. Nonetheless, I maintained, and continue to maintain, that OP Top Side was a poor tactical choice.

Most of the men who perished that fateful day did so attempting to defend or relieve OP Top Side (8 of the 9 who perished), and the kill ratio that day still favored the U.S. troops (“There were between 21 and 52 AAF killed and 45 wounded. Considering a clinical assessment of kill ratio can be a pointer to the level of risk associated with this VPB and OP. 21/9 = 2.33, 52/9 = 5.77 (2.33 – 5.77), and 45/27 = 1.67. These are very low compared to historical data (on the order of 10:1).”).

In previous discussions, one commenter weighs in with the following:

I definitely disagree with the idea of OP Topside as far-flung. It was only located 60 yards from the edge of VPB Kahler. In fact, the Company Commander was not pleased with the placement of OP Topside, but the LT believed placing the OP among the bounders in proximity to Kahler would make it easier to reinforce if a big attack did come. This in fact, proved to be the case as Topside was reinforced multiple times and proved the key to defeating the enemy attack at Wanat.

Strange analysis, this is. OP Top Side proved to be the Achilles heal of the whole VPB. Without having to relieve it, it is probable that most of the men who perished that fateful night would not have. More salient is this comment by Slab:

Where I think you hit the nail on the head is when you mention the terrain. The platoon in Wanat sacrificed control of the key terrain in the area in order to locate closer to the population. This was a significant risk, and I don’t see any indication that they attempted to sufficiently mitigate that risk. I can empathize a little bit – I was the first Marine on deck at Camp Blessing back when it was still Firebase Catamount, in late 2003. I took responsibility for the camp’s security from a platoon from the 10th Mountain Div, and established a perimeter defense around it. Looking back, I don’t think I adequately controlled the key terrain around the camp. The platoon that replaced me took some steps to correct that, and I think it played a significant role when they were attacked on March 22nd of 2004. COIN theorists love to say that the population is the key terrain, but I think Wanat shows that ignoring the existing natural terrain in favor of the population is a risky proposition, especially in Afghanistan.

Moving on to Bing West’s analysis of assigning blame for Wanat, he observes:

In my forthcoming book, The Wrong War, I describe Wanat in the larger context of a multi-year struggle for control of the mountainous region of eastern Afghanistan. Grave tactical and operational errors culminated in the Wanat battle. In The Wrong War, I conclude that at the operational level of war, Wanat “provided the classic case study of how insurgents conquer a superior foe. . . . The Americans intended to separate the people from the insurgents. Instead, the insurgents succeeded in separating the people from the Americans.”

Reporting from the Wanat area on Monday, Jaffe quoted the on-scene U.S. battalion commander as saying, “We fight here because the enemy is here. The enemy fights here because we are here. The best thing we can do is to pull back, and let the Afghans figure this place out.” The essential problem in the valley that includes Wanat was not a tactical mistake. The vexing nature of the tribal loyalties in eastern Afghanistan along the Pakistan border far transcends the conduct of a single battle.

The Army, however, was heavy-handed and obtuse in handling the reviews of the Wanat battle. Many officers disagreed with the reviewing generals who recommended the reprimands, and others disagreed with Cubbison’s draft. Combat veterans can make a reasonable case one way or the other. But for the Army as an institution to zig-zag invites criticism and raises unhelpful suspicions.

At a larger level, the incident illustrates the inherent problem in the promotion system of all the services. Errors happen in every war. Often victory goes to the side making the fewer mistakes. Everyone makes mistakes: Washington at Great Meadow and later Long Island, Lee at Gettysburg, Halsey and the typhoons, Chesty Puller at Peleliu, MacArthur and the Chosin, etc.

One of the three officers at Wanat cited by Petraeus for reprimand is a superb officer; I believe he would make a fine field general. It should be possible for a selection board to assess a reprimand, place it in balance against an entire career and continue to promote an outstanding officer. In business, CEOs fail miserably and are rewarded, illustrating the selfish, back-scratching nature of too many corporate boards of trustees; in the military, the services demand that an officer receive upwards of 40 fitness reports without a blemish in order to qualify for general officer selection. The services thus institutionally tend to reward the cautious, rather than the bold.

Separating the people from the Americans is also a bit exaggerated (or at least, somewhat irrelevant) when discussing the battle proper. Using only open source information, we can develop patterns of behavior with the Taliban that would have alerted U.S. commanders to expect such massing of forces. If I can do it, Army intelligence can do it. Good historiography brings in all elements of the problem to set the proper context, but even with proper context the basic outline of the problem doesn’t change.

There weren’t enough U.S. forces. It took too long to set up VPB Wanat. The Taliban worked much more quickly than did we in setting up their military operations. The U.S. sacrificed control of key terrain around VPB Wanat – and especially OP Top Side – in an attempt to provide proximity to the population. They summarily ignored both tribal counsel to set up the patrol base and tribal intelligence concerning massing of forces and imminent attacks, attacks that in fact followed tactics that could even be known by studying open source information.

Bing weighs in on holding officers accountable, and demurs insofar as it costs us openness and a learning environment. Whatever. I will observe that Marine Corps concepts of force projection and force protection are different and generally more aggressive. Aggressiveness could have helped in the Waygul valley, but their aggressiveness was limited by the lack of resources.

Col. Brostrom is right about holding commanding officers accountable. If his son objected to the placement of OP Top Side, so much the better. But whatever responsibility must be shouldered for the engagement, it increases with increasing rank. Pressing authority up and accountability down is the tactic of cowards. Refusing to hold higher ranking officers accountable for fear of creating a climate of suspicion runs both directions. If we cannot hold senior officers accountable, then neither can we (morally and rightly) hold lower ranking field grade officers accountable. And if we hold anyone accountable, higher authority means shouldering more of the responsibility. It’s just the way it is. This is true in the family, in business, in relationships, and in church. To claim that it could be anything else in the military is laughable and worthy of ridicule.

Prior:

Drone Front and Other Recommended Reading

Close Air Support of COP Kahler at Wanat

What Really Happened at Wanat?

Wanat Officers Issued Career-Ending Reprimands

Taking Back the Infantry Half-Kilometer

Second-Guessing the Battles of Wanat and Kamdesh

Wanat Video II

Wanat Video

The Battle of Wanat, Massing of Troops, and Attacks in Nuristan

The Contribution of the Afghan National Army in the Battle of Wanat

Investigating the Battle of Wanat

Analysis of the Battle of Wanat