Backwards Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan

BY Herschel SmithWell known and well-traveled independent journalist Philip Smucker has written an article in the Asia Times Online that warrants our utmost attention. But first, here is Philip’s take on the road situation in Afghanistan and its significance to successful counterinsurgency. This is required listening for anyone who really wants to understand the current counterinsurgency situation in Afghanistan.

Now to the Asia Times article.

In an instant … the mountainside above the rocky town of Doab erupted in muzzle flashes. For the next several hours, American soldiers in a convoy of 18 vehicles scrambled for cover as rockets and mortars rained down from the mountainsides and US helicopters swept in to evacuate the injured. Along with several of his best soldiers out of Fort Hood, Texas, Lieutenant Dashielle Ballarta, 24, displayed composure in the face of fire as his mortar team fell to Taliban bullets. Indeed, over the next five hours, three insurgent commanders with an estimated four dozen fighters would ambush the American soldiers at three different locations along a road with sheer drop-offs of 300 meters.

Only the fast reactions of US soldiers and medics would avert what commanders said could well have been a “slaughter” of American and Afghan forces. In the end, the Americans would boast that “we kicked some ass up there”, but the insurgents would also claim victory; dancing on the splintered remains of an abandoned US Humvee and vowing to keep the Americans from establishing a foothold north of their base in Kalagush, Nuristan.

This province, with its jagged peaks that rise two kilometers high into the blue skies above Pakistan, is known as Afghanistan’s “forgotten province”. But the intensity of the March 30 attack on a US military humanitarian aid convoy suggests that al-Qaeda and the Taliban have designated northern Nuristan as a key infiltration route and supply line for a growing insurgency.

Though Washington officials have castigated Pakistan for allowing al-Qaeda and Taliban “safe havens” to thrive along its own western borders, which abut Nuristan, this province’s vast terrain provides a similarly strong enemy sanctuary.

“The Taliban and al-Qaeda are moving through Nuristan at will,” said Lieutenant Colonel Larry Pickett, 46, a resident of McComb, Illinois, who dove for cover and took aim at the Taliban attackers in Doab, who had signaled their intentions a night earlier. “The north of the province is wide open and there is nothing to stop them.”

Some Western intelligence officers and Pakistani officials believe that the insurgents in Nuristan are part and parcel of a global guerrilla movement and may be protecting important al-Qaeda figures, possibly Osama bin Laden himself. “We can’t prove that Osama bin Laden is not there,” said Robin Whitley, 33, a US military intelligence officer in Kalagush. “A lot of people are on the lookout for a six-foot-four Arab, but when you don’t have anybody up there, you just don’t know.”

The convoy of 16 US Humvees and four Afghan trucks filled with security guards, left Kalagush on March 29 for a road convoy into the Doab district of Nuristan province. Leading the American contingent was naval commander Caleb Kerr, 37, who heads up Nuristan’s Provincial Reconstruction Team, Lieutenant Colonel Sal Petrovia, 37, and Lieutenant Colonel Pickett. Also along for the ride were Pentagon intelligence agents, including an unarmed member of the Human Terrain Team. The overnight mission intended to meet with local Nuristani officials, look at larger development projects and assess the possibility for more assistance …

The American strategy in Nuristan reverses the old US Marine Corps version of counter-insurgency; “clear, hold and build”. It stresses building first, with the hope that Nuristanis will eventually “see the light” and side with the Afghan government.

“There is a ton of bad guys in Nuristan, but we don’t have the resources to go after them all right now,” said Kerr. “We will not win by killing more people.”

The overnight development survey to Doab appeared to be going well until midnight when translators, who were listening to three distinct languages on radio intercepts, picked up chatter that indicated “the enemy” was planning to ambush US forces.

In the morning, meetings with senior officials continued and American engineers surveyed a new hospital and several schools.

Despite the presence of US-funded police in the town, dozens of insurgents managed to converge on the Americans from neighboring valleys, without being detected even by aerial drones specifically tasked with monitoring such movements. After seven years of careful observation, Taliban and al-Qaeda insurgents have learned to attack US forces when they are in remote terrain, far from their home base and short on air power.

At 11:15 am, just when the US air cover pulled off the scene to refuel, insurgents, holed up in hidden bunkers, began to fire rockets, mortars and small arms at the largest American patrol position; a circle of jeeps with guns pointing out. Sergeant Mathews, 24, from Chicago, quickly unpacked his mortar system, but enemy fire blasted his legs out from under him.

Platoon leader Lieutenant Dashielle Ballarta sprinted over. As medics assisted two wounded soldiers, the young lieutenant grabbed the mortar and pointed it towards muzzle flashes on the mountain. “It was pretty much ‘grab-and-point’ as the insurgents were so close he couldn’t calibrate their distance,” said Lieutenant Colonel Sal Petrovia, who had raced down to join the patrol team. “Our medics were treating the wounded, Specialist Shane McMath and Sergeant Mike Mathews, for 15 minutes behind a Humvee when the opposite mountainside opened up with muzzle flashes. They had snipers and I think they had been waiting for us to move to one side of the Humvees.”

After stabilizing the injured, the convoy moved down the road towards a pre-designated helicopter landing zone. A huge boulder blocked their exit. The Americans had to settle for a make-shift landing zone on a terraced wheat field, where a chopper could only send down a rope and harness.

“As we were preparing the wounded to be lifted out, we started taking fire again, this time on the retaining wall above the heads of the wounded soldiers,” said Lieutenant Colonel Petrovia. “The medics, Kurt Willen, 25 and David Myers, 23, covered the bodies of the two wounded soldiers and the rescue chopper had to back away as we called in two Apaches to suppress the enemy fire.”

Fighting continued as the US convoy snaked away, jeeps limping along with blown-out tires and dragging another disabled vehicle.

As the convoy negotiated switch-backs above cliff faces some four kilometers forward, insurgents launched yet another assault, rocketing the disabled vehicle, which still had four soldiers in it. Three-inch thick glass windows shattered and rockets bounced off the metal armor. “I looked around the bend and I could see Captain Tino Gonzales trying to keep his rear covered, ducking and dodging behind a tiny boulder as bullets pinged off the rock,” said Petrovia, who finally decided to abandon the disabled vehicle. An Apache was ordered to destroy it to prevent the Taliban or al-Qaeda from gaining access to sensitive military information.

At 8 pm, well after sunset, the US convoy puttered back into its base at Kalagush. Commanders said they had been taken aback by both the weaponry and the number of insurgents that had attacked them in Doab.

This is important and compelling journalism. Take particular note of the comment that the plan reverses the clear-hold-build strategy “with the hope that Nuristanis will eventually “see the light” and side with the Afghan government.”

Sadly, I believe that it won’t work. The force projection must first be implemented to ensure that the road-builders have safety, the aid workers have security, the infrastructure doesn’t go to financing the Taliban, and the soft counterinsurgency doesn’t in effect work directly against the kinetic operations at which the U.S. Army is working so hard.

Philip also reviewed David Kilcullen’s book Accidental Guerrilla. At the end of his review, he asks:

It may be that the imminent American surge in forces (at least 20,000 more troops on the way) could provide some of the answer, but if the US military goes in hard, particularly into the indomitable terrain of Nuristan, will it just end up creating more “accidental guerrillas?” One wonders what the Australian expert would advise on this point, just as US intelligence on al-Qaeda movements in Nuristan is increasing. As Kilcullen notes, “Our too-willing and heavy-handed interventions in the so-called ‘war on terror’ to date have largely played into the hands of this al-Qaeda exhaustion strategy.”

I think that this issue is largely a nonstarter. This issue may in fact be salient for some international engagements, but we were far from it in Iraq, and are extremely far from in in Afghanistan. On the contrary. We may have found the hornets nest, and the hornets must be eradicated. Reader and commenter TSAlfabet recently asked the following question.

Assuming that more than the 21,000 additional troops will not be forthcoming and, further assuming that the U.S. will apply some kind of cordon & secure strategy as discussed, where would you focus those efforts, at least initially? Kandahar? Helmand? In other words, since it is highly unlikely that the Administration is going to invest the necessary forces to secure all of the desired areas, what, in your view … are the most critical areas of A-stan that must be pacified and held in order to have a shot at prevailing long-term?

Great question. The Marines are obviously needed for the major combat operations in Now Zad. But more Marines are on the way, and they should be deployed to the Nuristan and Kunar Provinces (where the Korangal Valley is).

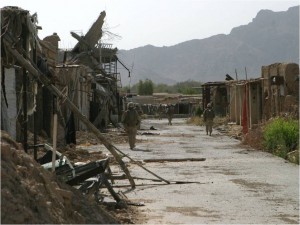

Firebase Phoenix overlooking the Korengal Valley

These are adjacent provinces, in the East area of responsibility, very near the Pakistan border and subject not only to indigenous Taliban fighters, but an influx of Taliban from Pakistan. We’ve struck the motherload.

Prior: