Confused Narratives on Marjah

BY Herschel SmithFrom Gareth Porter at the Asia Times.

For weeks, the United States public followed the biggest offensive of the Afghanistan war against what it was told was a “city of 80,000 people” as well as the logistical hub of the Taliban in that part of Helmand. That idea was a central element in the overall impression built up in February that Marjah was a major strategic objective, more important than other district centers in Helmand.

It turns out, however, that the picture of Marjah presented by military officials and reported by major news media is one of the clearest and most dramatic pieces of misinformation of the entire war, apparently aimed at hyping the offensive as an historic turning point in the conflict.

Marjah is not a city or even a real town, but a few clusters of farmers’ homes amid a large agricultural area that covers much of the southern Helmand River Valley …

The ISAF official said the only population numbering tens of thousands associated with Marjah is spread across many villages and almost 200 square kilometers, or about 125 square miles (editorial note, approximately eleven miles squared) …

So how did the fiction that Marjah is a city of 80,000 people get started?

The idea was passed onto news media by the US Marines in southern Helmand. The earliest references in news stories to Marjah as a city with a large population have a common origin in a briefing given on February 2 by officials at Camp Leatherneck, the US Marine base there.

The Associated Press published an article the same day quoting “Marine commanders” as saying that they expected 400 to 1,000 insurgents to be “holed up” in the “southern Afghan town of 80,000 people”. That language evoked an image of house-to-house urban street fighting.

The same story said Marjah was “the biggest town under Taliban control” and called it the “linchpin of the militants’ logistical and opium-smuggling network”. It gave the figure of 125,000 for the population living in “the town and surrounding villages”.

From Thomas Johnson and Chris Mason at Foreign Policy.

The war in Afghanistan, as we have written here and in Military Review (pdf), is indeed a near replication of the Vietnam War, including the assault on the strategically meaningless village of Marjah, which is itself a perfect re-enactment of Operation Meade River in 1968. But the callous cynicism of this war, which we described here in early December, and the mainstream media’s brainless reporting on it, have descended past these sane parallels. We have now gone down the rabbit hole.

Two months ago, the collection of mud-brick hovels known as Marjah might have been mistaken for a flyspeck on maps of Afghanistan. Today the media has nearly doubled its population from less than 50,000 to 80,000 — the entire population of Nad Ali district, of which Nad Ali is the largest town, is approximately 99,000 — and portrays the offensive there as the equivalent of the Normandy invasion, and the beginning of the end for the Taliban. In fact, however, the entire district of Nad Ali, which contains Marjah, represents about 2 percent of Regional Command (RC) South, the U.S. military’s operational area that encompasses Helmand, Kandahar, Uruzgan, Zabul, Nimruz, and Daikundi provinces. RC South by itself is larger than all of South Vietnam, and the Taliban controls virtually all of it. This appears to have occurred to no one in the media.

Nor have any noted that taking this nearly worthless postage stamp of real estate has tied down about half of all the real combat power and aviation assets of the international coalition in Afghanistan for a quarter of a year. The possibility that wasting massive amounts of U.S. and British blood, treasure, and time just to establish an Afghan Potemkin village with a “government in a box” might be exactly what the Taliban wants the coalition to do has apparently not occurred to either the press or to the generals who designed this operation.

In reality, this battle — the largest in Afghanistan since 2001 — is essentially a giant public affairs exercise, designed to shore up dwindling domestic support for the war by creating an illusion of progress. In reporting it, the media has gulped down the whole bottle of “drink me” and shrunk to journalistic insignificance.

Analysis & Commentary

The U.S. Marine Corps over the last several years in Iraq and Afghanistan has customarily been engaged in heavy combat operations. More than 1000 Marines perished in Iraq, most in the Anbar Province. Regardless, whatever the Marines are engaged in, they will officially hype their exploits and stretch the narrative, always redounding to the benefit of the Marines. It’s part of the history, mystique and political strategy of the Corps. The U.S. Marines are the best strike fighters and shock troops in the world. No matter, this narrative isn’t enough, and it is crafted and molded until the Corps takes on mythical proportions. The fact that their reputation precedes them and intimidates the enemy only justifies the strategy.

That most so-called journalists don’t know enough to be able to effectively cover the Marines is amusing, but reaches the point of being sad for analysts who spend time asking the wrong questions and reiterating what we all already know. Marjah is an approximately eleven mile squared area of operations comprising tens of thousands of farmers rather than an urban setting. So who didn’t already know that? The closest thing to a major urban center in Helmand is Now Zad. How is this “revelation” significant to worthwhile analysis of what the Marines are doing?

In Why are we in the Helmand Province? I addressed the notion that Marjah is a “worthless postage stamp” of land by pointing out that targeting Kandahar (as a population center) without a coupled effort to shut down the Taliban recruiting grounds and support network (as well as means of financing) would be analogous to giving the Taliban free sanctuary in Pakistan, just on a moderately smaller scale.

U.S. counterinsurgency strategists can claim until their last breath that counterinsurgency should be “population-centric,” but if we honestly believed that axiom we wouldn’t care about sanctuary in Pakistan. Control over population centers and good governance would be enough to marginalize the insurgents and render them powerless in spite of their sanctuaries – or so the doctrine claims.

But we know that the enemy must be stalked and killed, so we are in the Helmand Province, and Marjah was the last battle space for heavy kinetics. Policing of the population must now ensue in these areas. Kandahar will be next, and the buildup will be slow and deliberate, after, of course, we have finished with major operations in Helmand.

But if it isn’t one thing it’s another, and in addition to enduring bad analysis we must also deal with incomplete analysis that stops short of asking the hardest of questions. Consider this recent Washington Times editorial.

The recent battle in Marjah in Afghanistan’s Helmand province was a key test case for new rules of engagement that emphasized protecting civilians rather than killing insurgents. The town was taken, but whether that was because of the new rules or despite them remains to be seen.

The rules of engagement are probably the most restrictive ever seen for a war of this nature. NATO forces cannot fire on suspected Taliban fighters unless they are clearly visible, armed and posing a direct threat. Buildings suspected of containing insurgents cannot be targeted unless it is certain that civilians are not also present. Air strikes and night raids are limited, and prisoners have to be released or transferred within four days, making for a 96-hour catch-and-release program.

In Marjah, the enemy quickly adapted to the rules, which led to bizarre circumstances such as Taliban fighters throwing down their weapons when they were out of ammunition and taunting coalition troops with impunity or walking in plain view with women behind them carrying their weapons like caddies …

The fighting has wound down in Marjah, which may or may not validate the rules of engagement. Most of the local Taliban either melted away to the frontier or simply put down their weapons and are still there. The true test will come when NATO implements rules of disengagement. When coalition forces pull out, Marjah may well go back to being the Taliban stronghold it always has been, and those who cooperated with NATO and Afghan government authorities will be held to account.

True enough with respect to the rules of engagement (as we have pointed out before), this commentary ends with a non sequitur. It was predestined – the Marines were going to take Marjah, and there was nothing that the Taliban could do about it. The conclusion of the battle was firm and fixed regardless of the rules of engagement, and they have won Marjah in spite of the ROE and not because it it. The outcome of the operation says nothing to validate the ROE.

On the other hand, we all know that the Marines announced their offensive prior to its start for the specific reason of avoiding noncombatant casualties. That Taliban escaped was irrelevant. But is it? Will the Taliban simply slither away only to come back later and cause long term counterinsurgency problems in this area?

Will our focus on the population (to the detriment of killing insurgents) come back to haunt the campaign? Will we be dealing with these same insurgents later, walking with their women holding their weapons, knowing that the U.S. troops will not fire on them? What do the people of Marjah think about the rules of engagement? How long will this operation last, and will the horrible Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police be able to fill in behind the Marines?

The analysts at Foreign Policy called Marjah a “Potemkin village.” John Robb did this as well with Fallujah in a post entitled Potemkin Pacification (as best as I can tell, he took it down about as soon as it went up). There were a number of reductionist articles that sounded about the same when Operation Alljah began in Fallujah early in 2007. Most of these articles focused on the “horrible” conditions of Fallujah when the Marines locked it down.

In April – June of 2007 heavy kinetics ensued between the Marines and insurgents in Fallujah. The follow-on work involved heavy policing, gated communities, biometrics and neighborhood programs to watch and defend their turf. It was found that most IEDs were vehicle-borne, so the decision was made to prohibit vehicle traffic. When the population in a major urban center must walk everywhere, it provides a significant incentive to find and turn in insurgents and their weapons.

One narrative for counterinsurgency is that it must focus on turning the human and physical terrain into Shangri La, and if it doesn’t, it’s fake. Of course, it is the narrative that is fake. There will be heavy lifting in Marjah still to come, for it isn’t Shangri La. Fake narratives by so-called analysts will continue. But for the motivated journalist there are salient questions that must be answered.

As usual, Tyler Hicks is providing the best pictorial documentaries of Marine Corps operations in Helmand, and C. J. Chivers’ coverage is indispensable. But the Marjah narrative is yet to be written, much less the narrative for the Helmand Province (Now Zad claimed many Marine lives). Other than C. J. Chivers, we have yet to even approach anything that could be considered good analysis of the Marine Corps campaign in the Helmand Province, and Marjah remains fertile ground for reporting and analysis.

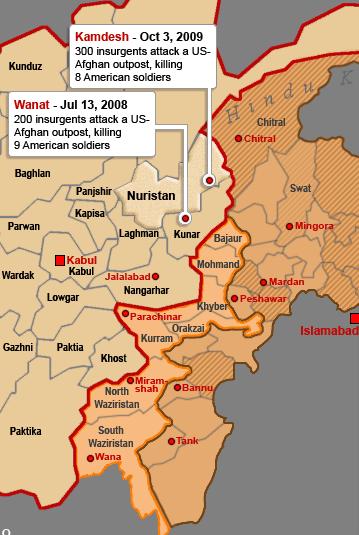

Prior Featured: Second Guessing the Battles of Wanat and Kamdesh

UPDATE:

Richard Lowry of Marines in the Garden of Eden fame writes to remind me that not all analysts missed the significant aspects of Marjah. His article Marjah – Another Fallujah? is worthy reading. Also check out his New Dawn.