Do we need a less aggressive force posture in Afghanistan?

BY Herschel SmithFrom Stars and Stripes:

Coalition troops will have to accept more risk as commanders push for a major turnaround in the Afghan war over the next 18 months, according to the commander of day-to-day operations across Afghanistan.

In an interview with Stars and Stripes, Lt. Gen. David Rodriguez said a renewed emphasis on developing a rapport with the Afghan people will mean an increase in the kind of “chai ops” — casual interactions with local leaders and residents, often over tea — that have been common in Iraq for the past year and a half.

This includes an emphasis on taking a less aggressive posture, removing helmets and body armor when appropriate, and living alongside Afghan security forces, Rodriguez said.

With insurgent infiltration still rife within the Afghan security forces, that’s a prospect that has some soldiers uneasy, but one Rodriguez said is necessary.

“It is certainly a risk, but the benefits are worth the risk,” he said.

That risk was underscored Tuesday, when an Afghan soldier killed a U.S. servicemember and wounded two Italian soldiers in Badghis province.

Rodriguez said that local commanders will decide what kind of posture to take and allowed that some situations still call for a stronger show of force, but he made clear that the ideal is to get as close to the people as possible.

“When you roll up into a village with one machine gunner on top of an MRAP, it’s not … too easy to interact with the people,” he said.

Analysis & Commentary

The transcript of the conversation with General Rodriguez doesn’t reveal use of the phrase “chai ops.” That’s a function of the reporting. But in a manner the actual transcript reveals even more troubling information about what Rodriguez thinks about counterinsurgency.

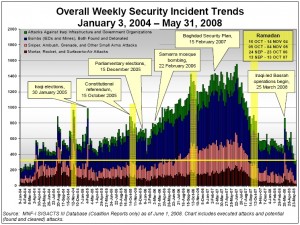

To be sure, the importance of the “awakening” in Anbar must be one of the elements of understanding that campaign, but the popular myth has grown up around Western Iraq that makes it all about drinking chai, siding with the tribes, going softer in our approach, and finally listening to them as they communicated to us. And the leader of this revolution in counterinsurgency warfare was none other than General Petraeus. We were losing until he appeared on the scene, and when he did things turned around.

We Americans love our generals, but this explanation has taken on mythical proportions, and is itself full of myths, gross exaggerations and outright falsehoods. While Captain Travis Patriquin was courting Sheik Abdul Sattar Abu Risha, elements of the U.S. forces were targeting his smuggling lines and killing his tribal members to shut down his sources of income. The tribal awakening had a context, and that was the use of force. As the pundits talk about the tribes, the Marines talk about kinetics.

Furthermore, the tribal awakening was specific to Ramadi. The beginnings of cooperation between U.S. forces and local elements came in al Qaim between Marines and a strong man police chief named Abu Ahmed. In Haditha it necessitated sand berms around the city to isolate it from insurgents coming across the border from Syria, along with a strong man police chief named Colonel Faruq.

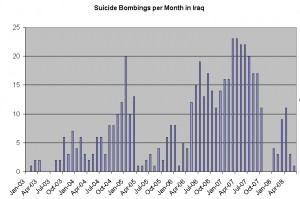

In Fallujah in 2007 it required heavy kinetics, followed on by census taking, gated communities, biometrics and heavy policing. Even late in 2007 Ramadi was described by Marine Lieutenant Colonel Mike Silverman as like Stalingrad. Examples abound, and as late as 2008, artillery elements fired as many as 11,000 155 mm (M105) rounds in Baquba, Iraq in response to insurgent mortar activity.

Whatever else General Petraeus did for Operation Iraqi Freedom, the U.S. Marine campaign for Anbar was underway, prosecuted before the advent of Petraeus, and continued the same way it was begun. The Marines lost more than 1000 men in combat, and this heavy toll was a necessary investment regardless of drinking chai with the locals.

What is so troubling about Rodriguez’s remarks is that historical revisionism has make its way into strategic planning for Afghanistan.

You’ve always got, no-matter where you are and everything, you’ve got somebody to check you. That’s what we have higher-headquarters for, no matter where you are; but a, there asked to make judgments, and again, there are supervisors and chain of command always checks everything, but this is part of the thing where you have to trust people to do the right thing sometimes because you can’t be there everywhere and there asked to make thousands of decisions but unfortunately one might not work out right but for the most part it’s gone pretty good and those leaders and supervisors are making good decisions and we think that’s the way to do it in the long run.

It’s kind of like making friends. Whether in Afghanistan, tea is important, whether it is the 3 cups of tea, like Mortenson says or anybody else but it’s just building those relationships …

Again, when you are with them, you make sure they are not doing anything wrong; serving themselves before they are serving the people.

Try to make it easy, it’s like a war crime, you don’t stand by and allow that to happen, so we don’t stand by and allow their governance to take advantage of the people; a lot of that is relationships, it’s about leadership, and just making sure they’re doing the right thing to serve their people …

Earlier on he mentions removal of body armor. The fact that he believes that the campaign for Afghanistan is anywhere close even to considering not wearing proper personal protective equipment is worse than preposterous – it is scary, because the lives of so many men depend upon decisions like this one.

In the transcript he does discuss pressing decision-making downward in the chain of command and allowing decisions like this to be made at the local level, but he doesn’t believe it. He reverts to the notion of every decision being checked by someone, and even seems to lament the fact that he (or others high in the chain of command) cannot be everywhere all of the time – as if his decisions would be the right ones even if his spirit he could be ubiquitous.

As we have discussion before, this micromanagement of the campaign is modeled on Western corporate conglomerate business practices, and relies on the mistaken notion that the higher up one goes in the chain of command, the better he is able to know, see, discern, ascertain, and divine all decisions made by all people concerning every event or decision under his charge. It assumes that promotion makes supermen, and this idea will become even more deadly on the fields of Afghanistan.

So the command situation is worse than simply mythologizing the importance of tea. We are now admitting to micromanaging the campaign from the highest levels of command (and lamenting that we cannot do it even more), and stupidly equating the failure to hold sovereign leaders accountable to our standards with war crimes. With leadership like this, the job of the Taliban is made even easier.

Prior concerning micromanagement of the military:

Micromanaging the Campaign in Afghanistan II

Micromanaging the Campaign in Afghanistan

Prior concerning intelligence and analysis failures of General Rodriguez’s staff: