From The Washington Times:

Afghanistan’s harsh and isolated Korengal Valley two years ago this month served as the setting for an unlikely U.S. military maneuver — a retreat.

The Army evacuated a network of hilltop platoon outposts, left them to the Taliban and started a war strategy devised by Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal, the top commander in Afghanistan in 2010.

[ … ]

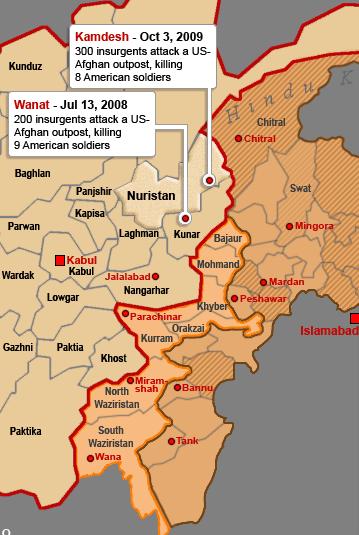

Today, the failed Korengal experiment is a factor in a new way of conducting missions in the east, which includes Kunar and 13 other provinces, and a 450-mile-long border with terrorist-infested Pakistan. The military calls it a “refocus” on finding and hitting the enemy, with less reliance on static valley outposts.

[ … ]

Nearly nine years into the war, the military had to acknowledge a big mistake.

“So what the commanders did, they took a very hard look at the east, with the help of the Kagans, who analyzed the terrain and the enemy to a level of detail that maybe had not been done in the past,” Gen. Keane said.

The Kagans are Frederick and Kimberly Kagan, a husband-and-wife analytical team who played a major role in developing and selling the Iraq surge.

In 2010, the U.S. command invited them to Afghanistan as an outside “red team” to tell the generals how operations could be improved.

Mr. Kagan, a military historian who taught at West Point, is a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Mrs. Kagan, who also taught at West Point, is president of the Institute for the Study of War.

The Kagans spent months in Afghanistan in 2010 and 2011. They traveled throughout the battle space to study the enemy and the tactics to kill them.

As the Kagans gave their advice, U.S. troops adapted.

“They refocused on the populated areas, which has meant coming out of some of the valleys,” Mrs. Kagan told The Times. “Troops rearranged so that they were massed in the key terrain in population areas in order to interact with the population, protect that population and really help abrogate the enemy by seeing to it they could not engage in the same intimidation campaigns that they were engaged in populated areas.”

Three main intelligence/strike targets emerged: “mobility corridors” through which the Taliban and allied Haqqani Network fighters moved; “support zones,” or safe havens, where the enemy planned and rested; and the areas around possible enemy targets.

“The Kagans did a better job in analyzing which were the ones the enemy was using and which ones were more important,” Gen. Keane said.

And what about the valleys such as Korengal?

“They are using strike forces and basically planned operations on occasion to go back into the valleys and remove pockets of the enemies when they grow sufficient to warrant military attention,” Mrs. Kagan said. “That is really what has changed in operating in the northern Kabul area.”

Mrs. Kagan said the operations of Army Col. Andrew Poppas, who led Task Force Bastogne last year, stand as a good example. He used “creative ways to mass forces” to go after the Taliban, she said.

Nine months into his mission, Col. Poppas talked to the Pentagon press corps from a base in Jalalabad. He gave three examples of combined strikes on identified safe havens that took territory away from the Taliban.

In Operation Bulldog Bite in Kunar’s Pech River Valley, “we successfully reduced the amount of insurgent attacks on the local populace and proved wrong the entire mystique that there were safe havens [for] the enemy,” he said. “We worked through each of the separate valleys, identifying, targeting the enemy network, predominately Taliban.”

Analysis & Commentary

Sounds nice, no? “Mobility corridors,” and “creative ways to mass forces”? The only problem is that despite what General Keane is saying, it hasn’t worked, and won’t work. Let’s begin with Highway 1, the most significant transportation and logistics corridor in Afghanistan, running between Kabul and Kandahar, and then on to other cities as the so-called “ring road.” Greg Jaffe recently authored a good piece at The Washington Post on this very road. The entire report is well worth the study time, but after a recent IED attack on Highway 1, U.S. forces wanted to know why a local farmer didn’t report the IED. The farmer’s reply is telling: “The Taliban were everywhere, including the Afghan army, the farmer replied. “There is no one I can trust,” he insisted.

On to RC South, which is supposed to be so much better off than RC East. The Marines are frustrated with the constant release of insurgents from prison, the changing strategies, and so much more. This report is disheartening.

I have seen courageous American soldiers get increasingly frustrated and cynical about the war. Last summer a Marine colonel in southern Afghanistan told me there was low morale among the troops. He said, “On an operational level, the soldiers are saying, ‘I’m going to go over there and try to not get my legs blown off. My nation will shut this bullshit down.’ That’s the feeling of my fellow soldiers.” The marine officer said, “The juice ain’t worth the squeeze.”

As for Keane’s claims for the success of the Kagan’s plans in RC East, there is near panic among Afghans in the Nuristan Province.

Local Afghan officials have called for a military intervention in the country’s northeast after scores of suspected Pakistani Taliban fighters overran several districts in Nuristan, a remote province bordering Pakistan.

Ghulamullah Nuristani, the security chief in Nuristan, says the militants captured the Kamdesh and Bargmatal districts of Nuristan two weeks ago and have torched dozens of homes and threatened to kill local villagers who work for the Afghan government.

Nuristani has called on NATO and the Afghan government to intervene, insisting that the small contingent of local police is powerless to stop the militants in Nuristan, from where U.S. forces withdrew in 2009.

“If anybody opposes them, the insurgents burn their homes and threaten to kill them. I have witnessed several houses being burned and seen many of the inhabitants beaten,” Nuristani says. “Until the government intervenes, we don’t have the resources [to fight back]. We can’t do it alone.”

It’s not clear where the militants are from. Nuristani says they are members of the Pakistani Taliban, who control the Pakistani side of the border alongside Al-Qaeda operatives and fighters from the Hizb-e Islami group headed by notorious former warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

Aziz Rahman, a village elder in Kamdesh, describes the militants as armed and wearing black clothing. He says the militants have set up a shadow government, opening local offices and collecting taxes from local residents.

“Kamdesh is under the control of the Taliban. The men in black clothing are here. They have opened a Department of the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice,” Rahman says. “They are teaching religious material and are telling people to do the right things. If people violate the rules, then they get punished.”

[ … ]

Mawlawi Ahmadullah Moahad, a member of parliament from Nuristan, issued a warning to the government on the deteriorating situation in Nuristan when he addressed parliament on March 24.

Moahad told parliament that the militants had crossed the border from Pakistan and had evicted hundreds of villagers from their homes and replaced them with families from the Pakistani town of Chitral, which is across the border in the Bajaur tribal agency.

It’s just as I had forecast for the Pech River Valley and Hindu Kush once U.S. troops left. A better chance to kill the trouble-makers in their own safe haven, we will never have. But we chose to implement population-centric counterinsurgency and withdraw to the cities, and then to top it all off, we decreased troop levels. It’s a sad, sad story that regular readers have seen well documented on the pages of The Captain’s Journal.

But what we see above is the fruit of our strategy. The chickens are coming home to roost. The people of Nuristan are in a panic, the Marines are fed up with the strategy, the farmers in the Kandahar Province are afraid of the Taliban, and just to make sure that you understand how parents and loved ones feel about the engagement, read the comments about the report from Nuristan when the author got the date for the battle at Kamdesh wrong.

by: Vanessa Adelson from: USA

March 29, 2012 23:59

Please get your facts straight. COP Keating was attacked in October 2009, not 2008. I should know. My son was killed during that attack. 300 Taliban attacked our small COP of about 50 soldiers. NOT ONE person from the village of Kamdesh let our COP know about the imminent attack. Some ANA were killed that day. Others turned their guns and attacked our soldiers. Others ran and hid. Let them ROT! Oh yeah, America….Pakistan is not a nation that should be considered our friend. Where do you think the Taliban came from that attacked my son and his buddies. Let’s just get the hell out of that country.

by: Dave from: Ft drum

March 30, 2012 16:52

Justice served. Keating was attacked repeatedly during 2008 as well and the first indicator of an attack was always the locals not showing up for work. No warnings. Screw em. My CO, Capt Yellescas died there in october 2008, a week after telling the local shura that America would abandon them to the Taliban if they didn’t start helping.

by: Cynthia Woodard from: Pa

March 30, 2012 00:23

The Battle of Kemdash was Oct 03, 09, not 08. My son was one of the 8 that were killed that day. Those people didn’t warn the soldiers that they were going to be attacked by 300+ insurgens. NOW they cry for our help. I say NO NO NO.

by: Knighthawk from: USA

March 30, 2012 00:44

All due respect – tough doo-doo. Too little too late we’re out of there soon and these people are screwed by their own failures to act when they had a chance, and their not the only area with the same story. The time for such calls were years ago but most of these villagers didn’t want to risk being involved then, or in many cases they did far worse by aiding the enemy (the very same people they are now complaining about) when US\NATO et all actually did try to secure their areas but this same population wouldn’t lift much of a finger to help themselves.

The fact they are crying foul now is pretty rich, but typical of the general afghan mentality.

Not a lot of love going around. And when you have lost morale among the Marines due to failed strategy and the parents and loved ones of men who have suffered are angry and resentful, you know that support for the campaign has evaporated.

It didn’t have to be this way, but we pretended that minimal troops and nation-building would work in Afghanistan. It’s been a costly pretension.