What We Learn From The Intelligence Committee Memorandum

BY Herschel SmithThis will only be a brief analysis, but I wanted to lay the groundwork for what I believe we learn from the recent Nunes memorandum.

Largely nothing. We knew most if not all of that already. Those who have been following the machinations of the deep state have know all of this for a very long time now. We know that certain high ranking officials inside the government – the government that is mostly not appointed, but rather, in for life, and a few who are appointed – have colluded and conspired to design a police state, couple federal, state and local law enforcement agencies into one by use of the JTTF and Fusion centers, weaken American foreign policy, empower the Muslim lobby, encroach upon and even destroy liberties in America, and started and prosecuted foreign wars in order to enrich themselves and their co-conspirators.

The wars in Northern Africa are an example of one such campaign, where nations were toppled in order to create “rat lines” of weapons, money, gems, oil and children, these “rat lines” only being the initial stages of more formal lines of logistics on a more industrial scale. Haiti was another such example, and the full story of TCF and CGI corruption in Haiti has yet to be told. Many of the people who have tried to tell the story have ended up dead. At the head of this conspiratorial network of taitors sits not just men like Comey and McCabe, but men and women at the State Department, DoJ, inside the U.S. military and the Council on Foreign Relations.

Again, we’ve known this for a very long time. For example, the YouTuber George (Webb) Sweigart called the involvement of the Awan brothers a full half year before anyone else did, and also provided excruciating and even painful detail on all of the military and political actions affecting the campaign to topple Northern Africa. We also knew that John McCain was involved in the campaign in Northern Africa. Thus, he said of the memorandum, “The latest attacks on the FBI and Department of Justice serve no American interests – no party’s, no president’s, only Putin’s.” Quite obviously, this is a misdirect and he doesn’t really believe this all has anything at all to do with Russia.

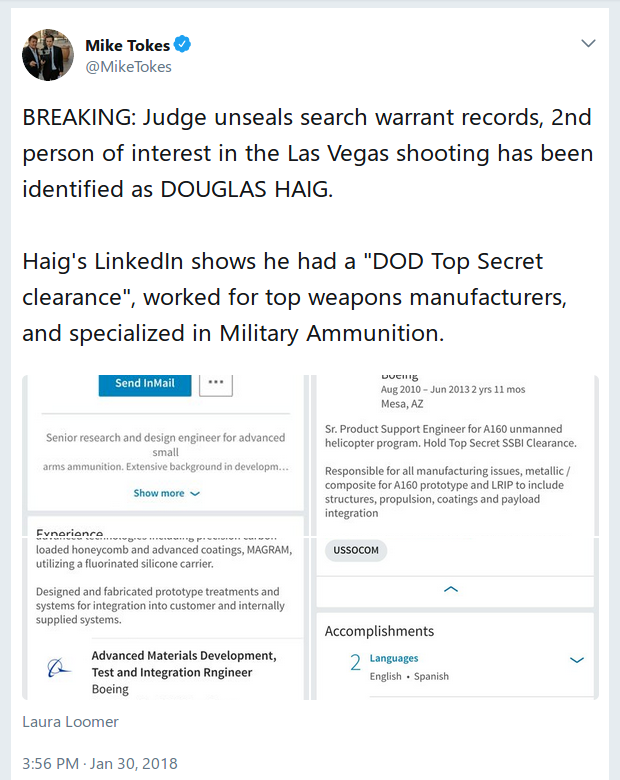

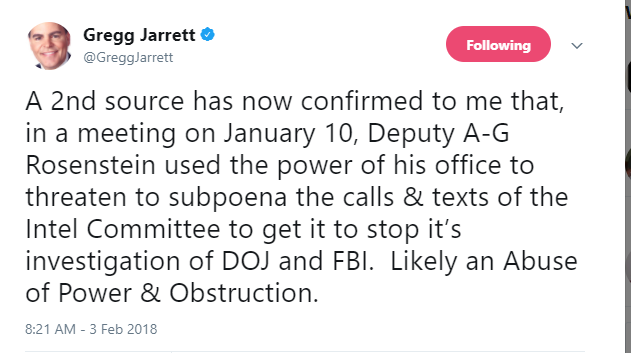

We also learned more about the involvement of DoJ personnel with the Nunes committee. Rod Rosenstein outed himself because he was apparently less disciplined than he needed to be. According to Greg Jarrett, he threatened the committee.

Much more troubling, however, is the degree to which the balance of Washington is in the pocket of the deep state. Is there any other reason for this?

Calling on Trump not to interfere in Mueller’s investigation, four Republican members of the House Intelligence Committee dismissed on Sunday the idea that the memo’s criticism of how the FBI handled certain surveillance applications undermines the special counsel’s work. Reps. Trey Gowdy (S.C.), Chris Stewart (Utah), Will Hurd (Tex.) and Brad Wenstrup (Ohio) represented the committee on the morning political talk shows.

Gowdy, who helped draft the memo, said Trump should not fire Rosenstein, and he rejected the idea that the document has a bearing on the investigation.

It appears that the deep state controls quite literally all of Washington, D.C., and all appurtenant departments, agencies, and personnel. It runs deep, far and wide, and its powers are immense. And that’s what we learn from the memorandum. We get no farther down the road to knowing what has happened. This is all the tip of the iceberg. But what we do learn if that when a little light is shined, the gargoyles, demons, monsters and pit vipers come out fighting. I think it’s a good thing for them to self-identify.