In the January / February 2009 issue of Foreign Affairs, Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates has a paper entitled A Balanced Strategy: Reprogramming the Pentagon for a New Age. It is a lengthy paper, and some selected quotes are extracted below, followed by a brief analysis.

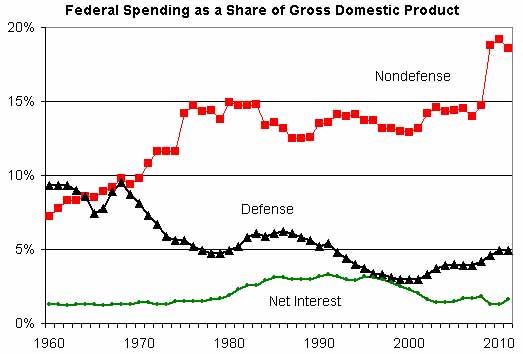

The defining principle of the Pentagon’s new National Defense Strategy is balance. The United States cannot expect to eliminate national security risks through higher defense budgets, to do everything and buy everything. The Department of Defense must set priorities and consider inescapable tradeoffs and opportunity costs.

The strategy strives for balance in three areas: between trying to prevail in current conflicts and preparing for other contingencies, between institutionalizing capabilities such as counterinsurgency and foreign military assistance and maintaining the United States’ existing conventional and strategic technological edge against other military forces, and between retaining those cultural traits that have made the U.S. armed forces successful and shedding those that hamper their ability to do what needs to be done.

The United States’ ability to deal with future threats will depend on its performance in current conflicts. To be blunt, to fail — or to be seen to fail — in either Iraq or Afghanistan would be a disastrous blow to U.S. credibility, both among friends and allies and among potential adversaries.

In Iraq, the number of U.S. combat units there will decline over time — as it was going to do no matter who was elected president in November. Still, there will continue to be some kind of U.S. advisory and counterterrorism effort in Iraq for years to come …

It would be irresponsible not to think about and prepare for the future, and the overwhelming majority of people in the Pentagon, the services, and the defense industry do just that. But we must not be so preoccupied with preparing for future conventional and strategic conflicts that we neglect to provide all the capabilities necessary to fight and win conflicts such as those the United States is in today.

Support for conventional modernization programs is deeply embedded in the Defense Department’s budget, in its bureaucracy, in the defense industry, and in Congress. My fundamental concern is that there is not commensurate institutional support — including in the Pentagon — for the capabilities needed to win today’s wars and some of their likely successors.

What is dubbed the war on terror is, in grim reality, a prolonged, worldwide irregular campaign — a struggle between the forces of violent extremism and those of moderation. Direct military force will continue to play a role in the long-term effort against terrorists and other extremists. But over the long term, the United States cannot kill or capture its way to victory. Where possible, what the military calls kinetic operations should be subordinated to measures aimed at promoting better governance, economic programs that spur development, and efforts to address the grievances among the discontented, from whom the terrorists recruit. It will take the patient accumulation of quiet successes over a long time to discredit and defeat extremist movements and their ideologies …

The recent past vividly demonstrated the consequences of failing to address adequately the dangers posed by insurgencies and failing states. Terrorist networks can find sanctuary within the borders of a weak nation and strength within the chaos of social breakdown. A nuclear-armed state could collapse into chaos and criminality. The most likely catastrophic threats to the U.S. homeland — for example, that of a U.S. city being poisoned or reduced to rubble by a terrorist attack — are more likely to emanate from failing states than from aggressor states.

The kinds of capabilities needed to deal with these scenarios cannot be considered exotic distractions or temporary diversions. The United States does not have the luxury of opting out because these scenarios do not conform to preferred notions of the American way of war.

The military and civilian elements of the United States’ national security apparatus have responded unevenly and have grown increasingly out of balance. The problem is not will; it is capacity. In many ways, the country’s national security capabilities are still coping with the consequences of the 1990s, when, with the complicity of both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue, key instruments of U.S. power abroad were reduced or allowed to wither on the bureaucratic vine. The State Department froze the hiring of new Foreign Service officers …

Yet even with a better-funded State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development, future military commanders will not be able to rid themselves of the tasks of maintaining security and stability. To truly achieve victory as Clausewitz defined it — to attain a political objective — the United States needs a military whose ability to kick down the door is matched by its ability to clean up the mess and even rebuild the house afterward.

Given these realities, the military has made some impressive strides in recent years. Special operations have received steep increases in funding and personnel. The air force has created a new air advisory program and a new career track for unmanned aerial operations. The navy has set up a new expeditionary combat command and brought back its riverine units. New counterinsurgency and army operations manuals, plus a new maritime strategy, have incorporated the lessons of recent years in service doctrine. “Train and equip” programs allow for quicker improvements in the security capacity of partner nations. And various initiatives are under way that will better integrate and coordinate U.S. military efforts with civilian agencies as well as engage the expertise of the private sector, including nongovernmental organizations and academia …

The United States cannot take its current dominance for granted and needs to invest in the programs, platforms, and personnel that will ensure that dominance’s persistence.

But it is also important to keep some perspective. As much as the U.S. Navy has shrunk since the end of the Cold War, for example, in terms of tonnage, its battle fleet is still larger than the next 13 navies combined — and 11 of those 13 navies are U.S. allies or partners. Russian tanks and artillery may have crushed Georgia’s tiny military. But before the United States begins rearming for another Cold War, it must remember that what is driving Russia is a desire to exorcise past humiliation and dominate its “near abroad” — not an ideologically driven campaign to dominate the globe. As someone who used to prepare estimates of Soviet military strength for several presidents, I can say that Russia’s conventional military, although vastly improved since its nadir in the late 1990s, remains a shadow of its Soviet predecessor. And adverse demographic trends in Russia will likely keep those conventional forces in check.

All told, the 2008 National Defense Strategy concludes that although U.S. predominance in conventional warfare is not unchallenged, it is sustainable for the medium term given current trends. It is true that the United States would be hard-pressed to fight a major conventional ground war elsewhere on short notice, but as I have asked before, where on earth would we do that? U.S. air and sea forces have ample untapped striking power should the need arise to deter or punish aggression — whether on the Korean Peninsula, in the Persian Gulf, or across the Taiwan Strait. So although current strategy knowingly assumes some additional risk in this area, that risk is a prudent and manageable one.

Analysis

The entire paper is worth studying, but Secretary Gates continues to build upon the theme of maintaining a balance between arming and training for near peer conflicts and irregular warfare. The theme is in keeping with his history, as he has convinced the current administration that the 183 F-22s already purchased are enough to fill the gap between now and the advent of the F-35 (which by all accounts is far outperformed by the F-22). The Air Force wants more, but will likely have to settle for 183. Gates’ pragmatic view is also in keeping with our own advocacy of the A-10 (which we believe to have been prematurely retired and entirely capable of performing another decade or two), but our advocacy is not entirely based on its performance in COIN. It is also a very capable tank killer, and can still function as originally designed. Not every aerial weapon has to be new, and outfitting the A-10 to bring it up to the digital age is quite enough for now.

Gates even goes to lengths that The Captain’s Journal isn’t prepared to go, in allowing money for the ill-conceived and (soon-to-be) ill-fated Army future combat system with its exoskeleton. We’ve made our desires know, i.e., lighter ESAPI plates with the same ballistic stopping power are a worthy investment, the exoskeleton is not (and is suited merely for erasing gender, strength and fitness differences in combat, not a laudable goal anyway). Kill the program, Secretary Gates.

Gates also pushes the notion that investment in almost-failed states is a worthy goal compared to the risk, i.e., the next attack that levels a city or kills civilians is more likely than not going to come from almost-failed states rather than stable ones. So far, so good. The Captain’s Journal has always been an advocate for Secretary Gates and will be so into the future.

But one cannot escape the sinking feeling that Gates is on another level in his understanding of things compared to the team that will surround him (excluding General Jim Jones). Gates clearly delineates between the army of State Department employees, foreign operatives and NGOs that are necessary for the proper engagement of almost-failed states and such notions for large state actors. The delineation is that while Gates works hard on the former, he doesn’t mention the later. The incoming administration appears by all accounts to believe that negotiations will suffice to dissuade bad state actors from their intentions. We have gone on record disagreeing with this.

One cannot escape the reality that Russia just might push for some version of its former global empire, that China might just decide that it has lost patience with Taiwan, and that Iran, no matter the size of the army of negotiators, will continue its push for nuclear weapons grade material. At some point we must consider that in addition to the ground troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, it’s prudent to have fleets in the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Aden along with Marines for CENTCOM ready reserve.

It’s going to be a difficult four years, we believe, but we feel certain about one thing. President-elect Obama couldn’t do any better than Secretary Gates, and his team is stronger for having him there, and would be profoundly weak without him. For those who have opined that the U.S. military is losing focus on conventional warfare with the institutional focus on counterinsurgency and stability operations, the argument is settled for the moment. We’ll do both, but we’ll focus for now on the campaigns we have at hand. And that’s that.