According to this article in The Washington Examiner, the prospects for the 2012 Federal Budget are bleak.

There are just 10 weeks remaining until an Aug. 2 debt ceiling deadline set by Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner. It’s a seemingly generous amount of time but too short in the eyes of some lawmakers, who are wrestling with how deeply to cut the budget and whether to increase the debt ceiling, the amount of money the government is allowed to borrow.

Scores of Republicans have pledged to vote against raising the nation’s debt ceiling if spending is not cut drastically, imperiling the measure in Congress and possibly forcing the government to default on its loans for the first time.

Despite months of debate, only one proposal has been advanced to address spending cuts, and that plan — written by House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, R-Wis. — may come to the Senate floor for a vote this week.

Ryan’s proposal would reduce spending by $6 trillion over 10 years and reform Medicare and Medicaid. But it isn’t expected to muster the 60 votes needed to pass, mostly because senators, including Republicans, are fearful of tackling popular entitlement programs with the 2012 elections looming.

The Federal Government is deadlocked, plain and simple.

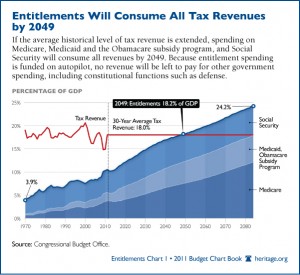

According to every conventional way of approaching entitlement spending, it is an impossible conundrum. Conservatives have many ideas about reforming or replacing such programs, but Republicans refuse to embrace them for fear of being tarred as heartless killers of old ladies and the poor. Liberals know in their hearts that these programs cannot, under any realistic scenario, continue as they are, but no Democrat is willing to even consider mild reforms such as the one posed by Rep. Paul Ryan for fear of being hacked to death by the Left as a sell-out or traitor to the People. So Republicans dither and delay while Democrats (and their media allies) demagogue the issue and distort the facts.

In fact, entitlement spending demonstrates, perhaps better than any other issue, the inherent weakness and fatal attraction in a central government that has badly strayed from its original, limited role. There is simply no way for the Federal government to make the required changes to Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid that will keep the Federal Government from falling off the financial cliff with Democrats in control of the Senate and White House and Republicans in control of the House. And it is not an option to wait until the 2012 elections possibly give control of all three branches to the Republicans. America’s fiscal problems will not stay put until then (and Republicans may not be trustworthy on spending reforms considering the last time they held all three branches).

With this impasse in view and the very real prospect that the Democrat-controlled Senate will go yet another year without passing a fiscal budget, I offer this suggestion as a way for Democrats and Republicans alike to escape their chains: turn entitlement spending over the States.

This is the perfect situation for punting the football and it makes absolute and total sense. It is the right thing to do. The ball is deep in our own territory, it is fourth and 50 yards to go and the coaches cannot make up their minds on any suitable play to call. “Punting” to the States is the only answer.

“Punting” in this context means that the Federal government recognizes it is simply not in a good position to administer programs such as Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare and, worse, is completely incapable of controlling them. The Federal government is far too big, too prone to waste and inefficiency and, most importantly, was never intended by the Founders to occupy the role of National Philanthropist. “Punting” means, too, that the States are far better equipped in many ways to decide what level of care and support to accord to their citizens and implement the corresponding programs.

So, for example, if California wants to endow all of its seniors with generous retirement and health benefits, let them do so as long as the burden for funding those lavish benefits falls squarely on the shoulders of Californians alone.

Consider entitlement spending in terms of a business: each State has to decide what benefits it can and cannot afford to dole out. If the State is too generous, it will eventually go “out of business” as millions move in to enjoy the generosity while millions more move out as their taxes inevitably skyrocket. If a State is too stingy, it will cease being an attractive place to work and live. Between the extremes is an enormous range of policy options and solutions that can be crafted to fit the unique circumstances inherent in every State. And, since most States are forced to balance their budgets each year by law, the State government will undertake entitlement spending with sobriety.

How could it work?

Such a change could not be done overnight, but it need not be terribly complex either. The first step would be along the lines of what Rep. Paul Ryan suggests in his proposal for Medicaid reform: block grants to the States. Florida, for example, might get a much larger grant based on 2010 Census numbers of its elderly population (and specifically its indigent population) than a demographically younger state. According to the 2000 Census, Utah is the “youngest” state, i.e., the one with the smallest percentage of elderly persons, while Florida is the oldest.

The block grants should also factor in existing poverty levels and not just the percentage of elderly in a given State. West Virginia has one of the higher percentages of elderly people but it also has one of the poorest populations. Other factors could be considered as well, such as populations of disabled or other, at-risk populations.

With this grant money, each state can use it as they see fit to provide for their at-risk populations.

This kind of block granting has the unique advantage of incentivizing better care for these at-risk populations. Say, for example, that Maryland develops a better, more efficient way of educating handicapped children. (This happens to be true). As this fact is known, more parents with handicapped children will move to Maryland which, in turn, will warrant more grant aid to Maryland to coincide with the higher, handicapped population. Resources get allocated to those locations that do the best job of serving their populations at the local level. Conversely, if another State does a terrible job with its care for handicapped children, then those parents will have every incentive to move to Maryland rather than remain in sub-optimal care elsewhere. A key feature would have to be some method for tracking the subject populations in each State to determine the block grant levels.

But can States be trusted with a large, no-strings-attached, grant of money? To continue the example, what if Maryland chooses to use the billions in Federal aid to plug the notorious gap in its annual budget? I submit that even a liberal, tax and spend haven like Maryland would never do this precisely because the Governor and state legislature are far more sensitive and accountable to Maryland voters than the U.S. Congressional delegation will ever be. Consider that, under the 2000 Census, the average Congressional district was comprised of 646,952 persons– far too many persons for individual citizens to hold the politicians accountable. Politicians are much more easily held accountable to their local constituency simply by virtue of the smaller numbers contained in each, State legislative district. It will, of course, be up to each State to decide how to best use the grant money and tough decisions will need to be made, but those decisions will be made far better at the state level where it is far more difficult for AARP to mobilize its members and bully politicians.

Giving entitlement spending to the States also makes sense in terms of perspective. When we look at Social Security spending, for example, at a national level, the sheer size and scope of the spending is completely disorienting. When speaking of hundreds of billions of dollars, it is nearly impossible to put the choices into concrete terms: who are these “millions of elderly” who will starve or go without medications? Why can’t we afford another $200 million for this program when we are already spending $800 billion? But when the debate is put at the state level, and more importantly, MY state level, things become much more focused. Supposing that Maryland receives $6 billion in grant money to cover social security, medicare and medicaid for Maryland citizens for the next year, how should that money be used? Am I willing to pay more in state taxes in order to ensure, for example, that 65 year-old Aunt Mary gets a social security check every month even though I know that she has an adequate retirement income from the Maryland Teachers Pension? Maybe. Maybe not. And will Aunt Mary join in marching on the state capitol to get that extra money even if it means higher taxes for me and her neighbors, friends, colleagues?

Some States will give that money to Aunt Mary and raise taxes to do so. Others may not. In the end, however, it will be far easier to come to grips with the many issues involved when we are dealing with specific populations in our own state and with the direct ramifications of those decisions in our own state.

Consider, too, the enormous savings to the Federal budget when the huge bureaucracies associated with Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid are allowed to shrivel up and die. The people employed at these federal agencies are not, necessarily, joining a bread line, however. With the block granting of funds to each State it is likely that persons with pension and healthcare experience will be in demand (hopefully by private firms that provide services rather than bloated State bureaucracies, but that is another topic). In any event, a reduction in federal personnel should be welcome relief to taxpayers everywhere.

Finally, the greatest benefit of transferring entitlements to the States is the effect upon Federal power and interference in the lives of ordinary citizens. When the Federal government holds the power of health care in its hands, it induces an unhealthy obeisance to the central power. This power needs to be split up among the 50 states so that ordinary citizens are empowered to hold their State officials accountable and rein in abuses. This principle can, of course, be applied across a wide spectrum of federal activities.

Hopefully the politicians in Washington, D.C. will pass the buck in this instance which would, ironically, be the right thing for once.